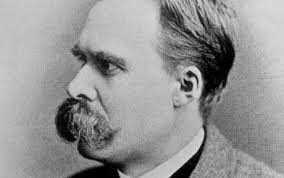

As anyone who reads my blog knows, I love (literary, film, and art) criticism. And, in many ways, I feel as if, through criticism, I am disclosing something about this or that story that has never be touched on before. And this thing that I am bringing out marks a direction or a tendency toward something transformational. Moreover, when I do critique I feel as if I take on the very tendency that I uncover in this or that book, story, film, etc. It’s not an act of indifference for me. This implies that my schlemiel theory project takes on a tendencies that I feel have been overlooked in this or that reading of the schlemiel. And not only is this a public, historical endeavor, it is also personal. A major inspiration for this approach to the schlemiel comes from Walter Benjamin and his notion of “immanent critique.”

Unlike any Walter Benjamin scholar, John McCole, in his exceptional book Walter Benjamin and the Antinomies of Tradition, looks into how Walter Benjamin understands tradition. As a part of his investigation, McCole looks into Walter Benjamin’s reception of German Romanticism. To this end, he provides the reader with a historical context to understand what German Romanticism looked to effectuate and what Benjamin drew from this movement. But what makes McCole’s reflection so incisive is the fact that he suggests that, for Benjamin, the Romantic Movement had a lot in common with the Youth Movement. Benjamin, as Gershom Scholem points out (and as we can see from Benjamin’s letters, essays, and notes from that period), was committed to this German Youth Movement. But as Benjamin himself points out in his essay on Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Idiot, this movement failed. And this filled Benjamin with regret. However, he managed, like Dostoevsky, to draw something out of the historical failure of the movement. As I have noted in another blog entry, what he came out with was the wisdom of foolishness and a sense of how utopia can become self-destructive. McCole points out that Benjamin referred to the Romantic Movement as a Youth Movement. And like the movement, he saw it as a failure. He saw this by way of criticism.

But this criticism was not merely a subjective reaction to failure. McCole tells us that Benjamin’s notion of criticism draws more on Kant than on the German Romantics and that this orientation put “inherited standards of orientation” into question:

Criticism meant objective reflection on the universal characteristics of the cognizing subject, not license to pass arbitrary judgments from an unexamined standpoint. Criticism did begin, however, by placing all inherited standards of orientation in question, rejecting dogmatic prescription of givens and absolutes whatsoever. (85-86)

Benjamin well-knew that the German Romantic movement took its inspiration, in major part, from the French Revolution. According to McCole, they “regarded the French Revolution as only the prelude…to a catastrophe that would bring an all-engulfing cultural transformation.” And “this expectation made them unable to accept any given, already perfected cannon of orientation”(86). For this reason, they put “Fichte’s Wissenschaftslehre and Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister alongside the French Revolution as the ‘greatest tendencies of the age’”(86).

McCole focuses in on the notion of a “tendency” since “the romantics stressed that they by no means offered perfected ideals but only pointers to the imperative of creating new norms and values.” To be sure, he argues that not just the Romantics but Benjamin himself was interested in “tendencies” (or “pointers”) to this imperative.

To be sure, McCole suggests that Benjamin saw himself as drawing a “tendency” out of this failed movement. He rescued this tendency from oblivion. And this rescue feeds into the reading of critique as something “positive.” Critique created “real historical change”: “critique for the early romantics, was the indespensible counterpart to real historical change, not an alternative to it”(87). In addition, critique looked to disclose the “metaphysical structure” found in the finite forms. Hence, for Novalis, to “romanticize” means “to extrapolate from the particular, finite form, until its absolute, metaphysical structure revealed itself.” One can argue that this what is meant by a tendency. In contrast to an ideal, it is a metaphysical structure that lay dormant in things, a structre than can be used to initiate historical change and transformation.

McCole shows how Benjamin’s notion of “immanent critique” is aimed at finding such tendencies. But these tendencies are not found in this or that historical period so much as in the artwork itself: “immanent criticism heeds the primacy of the aesthetics object’s own characteristics and properties”(89). The artwork – if read critically – can show us a tendency that can, in fact, lead the way to historical change since the artwork’s “immanent structure” provides a “corrective of all subjectivity”(90). And this implies that it “refracts and reforms all extrinsic forms that pass through it.”

As McCole points out, “immanent criticism” is productive and positive since, in pointing out these tendencies, it produces a new set of possibilities for the artwork that are latent in it. This suggests that, for Benjamin, the artwork is always incomplete:

Immanent criticism regards the artwork as essentially incomplete; it unfolds the work by making its potential qualities actual, its implicit features explicit. The result is to “reflect” the work, in the sense that criticism rises the object to a higher level of clarity and explicitness. (90).

In Benjamin’s words, the “reflection is awakened.” This is an act of romanticization since it transforms the tendency into a quasi-absolute that is, in itself, productive. This act, necessarily, is based on finding things in the decayed and forgotten artwork which can, of themselves (once awakened), alter history. This, perhaps, is the work of art which is “awakened” by criticism. In other words, Benjamin looks to awaken these “tendencies” in the work of art which “point to” the imperative of change.

Benjamin calls the observation of this awakening – caused by immanent criticism – “magic observation.” And, as McCole notes, this experience of observation is “interactive” – and, in addition to raising the critics consciousness, the observation can also be “incorporated” into the critic’s self. This was much like Novalis for whom, “the true experimenter” is one who nature “reveals itself more perfectly” if and only if he harmonizes himself with what he observes through criticism. In other words, through the critic who becomes one with his “magical observation” (prompted by immanent criticism), one can experience the tendency toward revolution.

This model works well with schlemiel theory. Following Benjamin’s lead, I think “immanent criticism” is of great use since the schlemiel is a character which seems to have decayed. Yet, as Benjamin knew, comic characters show us a tendency toward revolution. By employing an immanent criticism to the schlemiel – in this or that novel, short story, play, or film – the critic can have a “magical observation” of sorts that can be witnessed by readers.

Perhaps this is saying too much, but there is a lot of truth to it. A schlemiel theorist should show us a tendency to change. But this can only be found by way of rescuing the schlemiel from oblivion. And this is a major part of my project otherwise know as schlemiel theory. I do believe that this rescue can have a positive historical effect. But that all depends on how my project is witnessed by others and whether it taps into a historical possibility (or possibilities) that has (or have) been overlooked. As one can imagine, I have hope, as did Benjamin, that the trash that I have found (in this case, schlemiel trash) may indicate a possibility or tendency that has been overlooked. And like Benjamin, I understand that this “magical observation” is based on “awakening” this tendency by way of “immanent criticism.”

This “magical observation” of the schlemiel’s awakening is my risk; and it is the risk of schlemiel theory.