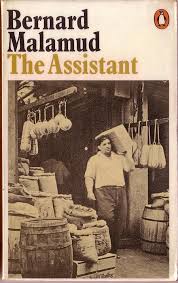

One of the greatest things Bernard Malamud provides the reader of The Assistant with is an acute sense of how complicated it is to become a good person. The schlemiel in the novel, Morris Bober, is the model for goodness. His endurance of suffering, bad luck, and failure show the reader a character who, though comical, is in many ways saintly. But it is not his suffering so much that makes him a saintly-schlemiel as the fact that he trusts the other. We see this most clearly when Bober gives Frank, who becomes his assistant, a chance to do good.

As I have pointed out in the last blog entry, Frank is culpable for robbing Bober with Ward. And this may have prompted him to show up on Bober’s doorstep to help him out and become his assistant. However, as the story goes on, we see Frank struggle with being good. Even though he admits to himself that he has done wrong in the past, he still steals money from Bober. Moreover, he doesn’t speak to him and confess that he has done wrong. This lack of communication is, as I noted in the last blog, the missing link to fully doing teshuva (repentance). His effort to become good must include being good in thought, speech, and action. As the novel shows, he is partial and until he speaks and stops stealing, his good feelings or thoughts are not enough.

After telling himself that he was a “victim” of Ward’s anti-Semitism, he decides that he wants to have a new beginning. This decision is the seed of his teshuva. After returning money to the register, Frank starts feeling good:

After ringing up the six bucks, to erase the evidence of an unlikely sale he rang up “no sale.” Frank then felt a surge of joy at what he had done and his eyes misted. In the back he drew off his shoe, got out the card, and subtracted six dollars form the total amount he owed. He figured he could pay it all up in a couple-three months, by taking out of the bank the money – about eighty bucks – that was left there, returning it bit by bit, and when that was all used up, giving back part of his weekly salary till he had the debt square. The trick was to get the money back without arousing anyone’s suspicion. (159)

In the midst of his joy of doing good, Helen, Bober’s daughter, calls him up on the phone. As I noted before, he has a crush on her and she likes him. Bober lets this slip by while Ida doesn’t. Helen, in her phone call to him, confesses that she would rather hang out with him that with Nat Perl, a Jewish boy who is likely to become a success in life. Helen’s mother, Ida, would rather she marry or hang out with Nat while Bober trusts, perhaps foolishly, that Frank would be harmless. He believed that Frank was a harmless poor person, like himself.

In this chapter of the novel, we see that Bober’s idealization of Frank is false on two counts. Thinking of when he will meet Helen, Frank realizes that he will need money for the cab to get home from the date. He then decides to steal some money from the register:

Frank had decided he didn’t like to ask Helen for any money – it wasn’t a nice thing to do with a girl you liked. He thought it was better to take a buck out of the register drawer, out of the amount he had just put back. He wished he had paid back the finve and kept himself the one-buck bill. (161)

But when he does this, Bober, for the first time, catches him in the act and decides to confront Frank: “The grocer held his breath for a painful second, then stepped inside the store”(161). Frank lies to Bober and says there was a “mistake”(161). But Bober pushes him on this lie. Bober says flat out that “this is a lie”(161). Bewildered, Bober, once again, asks Frank why he lied (Frank, recall, stole rolls and milk at the beginning of the novel without telling Bober, but Bober let it go on account of Frank’s poverty; now, however, Frank is no longer a homeless poor man). But Frank still can’t admit to it and insists that it was a “mistake.” Frank asks for another chance and Bober says “No.” Bober becomes sad and tells Frank to leave:

Frank stared at the gray and broken Jew and seeing, despite the tears in his eyes, that we would not yield, hung up his apron and left. (163)

Following this, Frank goes out to drink before he meets up with Helen, Bober’s daughter. When Frank doesn’t show up on time, Helen starts to worry (165). And, out of nowhere, Ward shows up. Ward, drunk, accosts Helen, she turns him away and, in the heat of the moment, he makes sexual advances. Helen fights back:

Struggling, kicking wildly, she caught him between the legs with her knee. He cried out and cracked her across her face… Her legs buckled and she slid to the ground. (167)

Frank emerges out of the trees and hits Ward. Ward runs off. Helen feels saved, kisses Frank, thanks him, and “holds him tightly.” But then Frank does the unseemly thing and although she tells him no, he insists that he loves her so much that he must have sex with her. He “stopped her pleas with kisses…”(168). However, the last words are hers: “Afterward, she cried, “Dog – uncircumcised dog!”

These are the last words of the chapter. They indicate a separation of Jews and Gentiles that brings back old hatreds and ancient memories of oppression. They also show us how Frank has broken with all possibilities for goodness. He is in a low state and in need of redemption.

In the following chapter, we see Bober, his wife, and Helen mourning Frank’s departure from the store…and the possibility of goodness. They are saddened as they all, with the exception of Ida, had hope that Frank could turn things around.

Frank is deeply hurt. And at home that night the narrator tells us that Frank “cries out”(174). The narrator points out that Frank’s thoughts “stank” and “the more he smothered them the more they stank”(174). This stink is also physical. We learn that his body stank and that it was lodged in his nose. His body is repulsive: “The sight of his bare feet utterly disgusted him”(174). And his thoughts “were killing him. He couldn’t stand them.” Frank then experiences major ambivalence. He wants to leave the city, but he feels he must stay. He wants forgiveness and replays in his mind what he will tell Helen (174). In addition to this, he imagines what Helen will say and this drives him mad. He looks in the mirror and stages this dialogue. He “faces” failure:

Where have you been, he asked the one in the glass, except on the inside of a circle? What have you ever done but always the wrong thing? (174)

The narrator compounds things by noting how he also betrayed Morris and had failed to do the right thing on many occasions. Thoughts about all of these failures leaves him, so to speak, with a stink:

His thoughts would forever suffocate him. He had failed once to often. He should somewhere have stopped and changed the way he was going, his luck, himself, stopped hating the world, got a decent education, a job, a nice girl. He had lived without will, betrayed every good intention. Had he ever confessed the holdup to Morris? Hadn’t he stolen from the cash register till the minute he was canned? In a single terrible act in the park hadn’t he murdered the last of his good hopes, the love he had so long waited for – his chance at a future? His goddamn life pursued him wherever he went; he had led it nowhere….The self he had secretly considered valuable was, for all he could make of it, a dead rat. He stank. (175)

Meanwhile, Helen feels regret for having trusted Frank. The narrator, in a similar fashion, writes a paragraph full of questions about how she had been duped. This leads to her feeling a “violent self-hatred for trusting him”(176).

In the midst of all this self-loathing over mistrust and failure, yet another trauma emerges. Bober goes to sleep in his house, but since he forgot to light the gas he is exposed to noxious fumes. Frank smells the gas coming from Bober’s home and immediately springs up to save him. Frank does his best to revive him and succeeds in saving his life.

Although everyone is angry at Frank, the fact that he saved Bober’s life creates an awkwardness between them. And when he comes back the next day, we can see that Ida is agitated with his presence. But he gives her back all of the money he took and says he wants to visit Bober in the hospital. However, Ida doesn’t let him leave so easily and orders him to stay away from Helen.

When Frank finally faces Bober and confesses to him, we see a different person. To be sure, the whole novel Frank wanted to say something. But now more than ever Frank feels he can speak. He wants to be trusted by Bober, the honest schlemiel. However, as in the Jewish tradition, Frank’s apology is not enough. It needs to be accepted:

“Morris, Frank said, at agonizing last, “I have something important to tell you. I tried to tell you before only I couldn’t work my nerve up. Morris, don’t blame me now for what I once did, because I am now a changed man, but I was one of the guys that held you up that night. I swear to God I didn’t want to once I got in here, but I couldn’t get out of it. I tried to tell you about it – that’s why I cam back here in the first place, and the first chance I got I put my share of the money back in the register – but I didn’t have the guts to say it…You can trust me now, I swear it, and that’s why I am asking you to let me stay and help you.”(198)

Morris Bober, however, is not astonished. He tells Frank that he figured it out long ago but didn’t say anything! Regardless, Frank’s pleas for forgiveness don’t stop: “But the grocer had set his heart against the assistant and would not let him stay”(200). It seems that Frank’s efforts to do teshuva will require him to suffer more and this is something he learns from Bober who lives the life of a schlemiel where failure is an everyday reality and where trust is a premium. In effect, Bober’s refusal to accept Frank’s apology is a gift that will, in the wake of Bober’s death, prompt Frank to convert and become a Jew. What is the meaning of this? Is Malamud suggesting that to be forgiven and to regain trust, the criminal must become the victim? Must Frank, in effect, not just become a Jew but…a schlemiel?

….to be continued