Is Seth Rogen giving the schlemiel a bad name or…another name? To be sure, I’ve written several blog-entries on Rogen-as-Schlemiel. Before I saw Rogen and Franco’s parody of Kanye West’s Latest video, I was already on Rogen’s trail. And, to my understanding, he, along with Judd Apatow and others, were looking to revise the schlemiel character. Their formula – the same formula used by Woody Allen since Hollywood Ending (2002) and Anything Else (2003) – was to cast the main character as a schlemiel (a half-man) in the beginning of the film, but by the end of the film he would become a man. This contrasts to Woody Allen’s older formula – which we see in Zelig or Annie Hall, amongst other films – which is to cast a main character who starts and ends the film as a schlemiel. This formula is actually older than film; to be sure, we find it in Yiddish folklore and throughout Yiddish and Jewish-American fiction. However, some authors, like Phillip Roth, have decided to leave this character behind in their later novels. Despite this, the schlemiel lives on in fiction, film, and television. Even the famous talk-show star, Howard Stern often reminds his audience (which numbers in the millions) that regardless of how successful he is, he is still “half-a-man” (that is, still a schlemiel).

Rogen, it seems, is confused about whether he should cast himself as a half-man becoming a full man – as we see in Knocked Up (2007), Zack and Miri Make a Porno (2008) or The Green Hornet (2011) – as a half-man becoming a little more of a man – as in Guilt Trip (2012), or as a man who has his share of bad luck – as in Take this Waltz (2011). Now, with this video, we can add another position: casting himself as a woman (namely, Kim Kardashian).

By casting himself as a woman or gay (both?), Rogen, it seems, is taking the schlemiel into new territory. And he is disseminating a new image of this character on a wide basis. After all, the video has seen over 2 million views over the last 24 hours and will likely get more hits over the next day or two.

But is this new ground?

It’s not. To be sure, the schlemiel has often been cast as an effeminate character. This goes back to Mendel Mocher Sforim’s Yiddish novel Benjamin the III. In that novel, written in the mid-19th century, the main character plays a Don Quixote kind of character who models himself on the tales of Benjamin of Tudela who is best known for his travelogue. This book – apparently written in the 12th century – was based on his ten years of travel around the world. He describes the world to his Spanish compatriots. But in Sforim’s book, the schlemiels think they will go on a similar journey when, in fact, they don’t even leave the “Pale of Settlement” – an area where Jews were, for over a century, confined. In the novel Benjamin refers to his make travel partner as his wife and at times trials him like a wife. And his partner goes along with it, too.

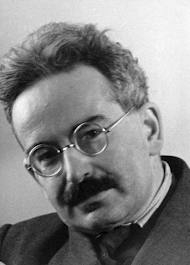

Following this novel, we see more and more effeminate portrayals of the schlemiel. To be sure, this character is often cast as half-a-man and is more sensitive and vulnerable than others. And although Milton Berl cross-dressed, he always retained his male aspects by way of his speech. As Ruth Wisse points out, regardless of how vulnerable they are – or even if they cross-dress – schlemiels often win an “ironic victory” over the world and history which excludes them; but they don’t do this by being entirely passive. They do this by way of speech. As many a schlemiel joke or story will show you, the schlemiel is a master of words and loves to play with them. In this, at the very least, there is something redemptive. A Jews dignity, though trampled on in this or that story, is retained through such verbal humor. And this comic act, so to speak, indirectly speaks truth to power.

What Seth Rogen has done here, however, is to make himself totally passive. To be sure, he, like Kim Kardashian in the video, doesn’t really say anything. Kanye or James Franco speak; Kim and Seth are submissive. And they are both being ridden by a man. They are both in a Missionary kind of position –even though, for all intents and purposes, it’s on a surreal motorcycle.

In addition to this, I’d say that Rogen is not the first “heavy” schlemiel. There are many others before him – although many people often associate the schlemiels body with wiry people like Woody Allen, Jack Benny, or Ben Stiller (to name just a few). Regardless, in comparison to Kim Kardashian’s “perfect” body, we see Rogen’s hairy and heavy body as its anti-thesis. And when Rogen makes sexy faces, we can’t help but snicker.

But the joke is really on Rogen and the schlemiel. It is not on Kanye and Kim. And it isn’t even on James Franco. If anything, the schlemiel may cross-dress or play the half-man in many novels, films, or stand-up routines. But what a schlemiel won’t do is lose speech, which is the schlemiel’s greatest ally since it keeps total passivity at bay.

For this reason, I had a hard time watching this only as parody (which it obviously is) since, in many ways, it seemed to be effacing the schlemiel I have grown to love and even respect. So, while Kanye and Kim may have found it funny, I don’t. Because the joke is ultimately on the schlemiel, not them.