These are the words of Jack Benny – whose real name was Benjamin Kubelsky. And they are – more or less – an affirmation of ethnic humor. He thought of such humor as – in the words of Lawrence Epstein – “socially redemptive.” They were spoken in relation to racist and anti-Semitic claims made against Jews and African-Americans during the depression; and the characters that Benny found “socially redeemed” ethnic humor were Mr. Kitzel (a character who “Jewish” mannerisms) and Rochester an African-American character. The two, in fact, shared many skits. Lawrence Epstein points this out by way of Benny’s own words – in retrospect – on these characters: “I never felt and I do not feel today that Rochester and Mr. Kitzel were socially harmful. You don’t hate a race when you are laughing at it.”

Given the fact that many an anti-Semite laughed at Jews, this is an astonishing claim. One of the major anti-Semitic claims made against Jews is that all Jews are weak. Sander Gilman, in The Jew’s Body, points out how Jewish men were often depicted as effeminate. This, to be sure, is ethnic humor (of a very negative, biased sort).

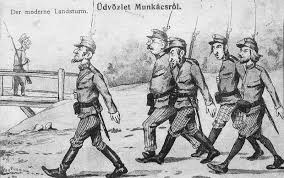

When Jews were represented, their bodies are pictured in relaxed, comic, and effeminate postures. The comic strips were used, in these pieces, to laugh at Jews and ridicule them for being outsiders whose bodies were not “normal” and “graceful” like their fellow German citizens.

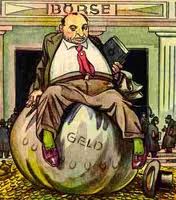

Ethnic humor was used to invoke hatred of Jews in Germany from the Enlightenment to the Holocaust. Caricaturing Jews as power hungry, overweight, scheming, cheap, and weak had a horrific and a comic edge (aimed at exclusion):

But this, Epstein claims, was reversed on American soil. As Jews learned, the best place to challenge the representations of the Jewish body was on the American stage where weakness could become a Jewish trait that was not so much deplorable as worthy of compassion. And this compassion served, in some sense, to create a way for Jews to be accepted into an American society that had become, with the depression, hostile toward the Jews. This observation, it seems, finds much resonance in David Biale’s definition of the schlemiel as “charming.” It also echoes Hannah Arendt’s descriptions of Charlie Chaplin and Heinrich Heine’s “lord of dream” – exemplary schlemiels in the “hidden tradition.”

Lawrence Epstein makes a case for this in The Haunted Smile. He finds the inversion of an anti-Semitic characterization of Jews as weak – which we see above in the negative ethnic humor and caricature – by way of the weakness in Jack Benny’s comic performance. Benny, argues Epstein, found a way of countering anti-Semitism by way of two routines that actually adopted anti-Semitic stereotypes and inverted them.

The claim that Jack Benny’s comic act inverts American culture was first made by Susan J. Douglas: “Douglas reads the character as an attack on both masculinity and upper-class pretensions.” (For more on the topic of masculinity, comedy, and inversion see my blog entry on Daniel Boyarin’s reading of the father of the Hasidim: the Baal Shem Tov.) Epstein agrees with her that “the Benny character subtly attacked the leaders without ever being political.” And, in the process, he affected audiences without their even knowing it. He spoke to the public’s anger at being duped by their leaders who worked in cahoots with the stock market to create the Great Depression. But this anger was misdirected at the Jews of the time.

Benny did address and invert this anger by adopting and playing on stereotypes; and did this, specifically, through the schlemiel:

Benny mocked his own prowess with a violin, a musical instrument widely identified with Jews, and the Benny program produced two Jewish ethnic stereotypes as characters, Mr. Kitzel and Schlepperman.

Interestingly, Epstein says many people in the American audience didn’t even know he was Jewish. Rather, he played with images that had some kind of, as the postmodern sociologist Pierre Bourdieu might say, symbolic power. And, in relation to them, he gave Jewish stereotypes a more positive valence. That said, the expressions he came up with went viral and this had a good effect of, in Epstien’s view, defusing anti-Semitism.

For instance, when Mr. Kitzel cried out, “with a pickle in the middle,” such diffusion was at work. The expressions of Mr. Kitzel – the expressions of a schlemiel- did this cultural work. Audacious, odd phrases, in a Lyotardian sense, created a new “idiom” which, when repeated, gave Jewishness a new currency that it never had before (even though much of the American audience may not have picked up that it was a “Jewish” dialect that was being displaced).

To be sure, it is Mr. Kitzel’s absent-mindedness, which he is blind to, that is most charming. The audience’s response, Epstein says, is “empathetic” as opposed to “being antipathetic.” And this small element of empathy, argues Epstein, was enough to sway an American audience to accept not necessarily Jews as Jewishness (which, he claims, they may not have even consciously noticed) as something non-threatening.

The key to this charm was the identification with Jack Benny, the man-child schlemiel. The lesson we learn is that the schlemiel’s charm can be used as a way of fostering a kind of American populism that is based on an openness to weakness. We see this in Benny and we see it in the latter part of the 20th century in Woody Allen, Ben Stiller, Adam Sandler, and Seth Rogen (amongst many). The strategy of weakness is the strategy of assimilation and a way of deflecting anti-Semitism, or so it seems. However, this appears to miss the fact that, today, Jewish comic traits of weakness are no longer Jewish. You can find them everywhere. And this can come out in a turn of phrase, a gesture, or a situation. Take, for instance, Napoleon Dynamite or the Dude from the Cohen Brothers film The Big Lubowski:

Their way is the way of the peaceful, inept, yet (unconscious) charming warrior. While the association of ethnicity with weakness seems to have fallen away in America, weakness (as such) remains. I’ll leave it at that….