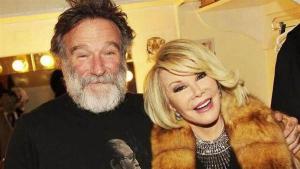

The death of Joan Rivers has left its mark. Many of us have been searching for words. And, as with any death, we try to remember the best things about her. So many things come to mind, but how, I wondered, could I find words. This was too much. After Robin Williams death, I was besides myself and now Joan. All of the joy they brought to my life, the life of my friends, and my family. It felt as if it was all gone.

….

As soon as I heard the news of Joan’s death, I went immediately to twitter to check the comedians I follow for insights into who she was and what she did. After learning of her death, Mel Brooks tweeted: “Joan Rivers never played it safe. She was the bravest of them all. Still at the top at the end. She will be missed.”

Something about Brooks’ words resonated deeply in me. Yes, he was right. She never played it safe. She was the bravest of all. Her bravery, however, didn’t have to do with the comic boundaries she broke with her words so much as with her person. As a female comic, she took risks that broke boundaries for other women comics. And this, I thought, is what Brooks meant when he said she was “the bravest of them all.” And this needs to be recognized and remembered in the wake of her passing.

Lawrence Epstein, in his book The Haunted Smile, gives Joan her own chapter. The title of the chapter and its subtitle suggest that with female comedy had radically changed Jewish comedy in America: “Kosher at Last: Jewish Women Comedians.” Epstein begins his chapter without mentioning Joan’s name. Joan is presented as a woman without a name (“she”):

She was still struggling for recognition as a comedian. Billed as “Pepper January – Comedy with Spice,” she was faced with a hostile audience. The raucous men seated at the tables had a very definite set of ideas about the men and women who stood in front of them to provide entertainment: the men were supposed to tell jokes, and women were supposed to take their clothes off. Here, though, was this thin, loud woman trying to tell them jokes. The audience members began booing. (253)

After writing this description of “her” act, Epstein tells us her name: Joan Molinsky. As with many Jewish-American comic artists (and artists in general), she had to change her name. She went to her agent, Tony Rivers, and he told her that in order for her to get recognized as an American artist she had to change her last name to Rivers. From then on, she was Joan Rivers.

But the name change wasn’t enough. As Epstein notes, after World War II Borsht Belt humor, which Brooks, Reiner, and Allen (amongst many other famous comedians) participated in, “instilled a deep hostility toward women and mothers”(254). But these comedians weren’t doing something that went against the norm. Epstein tells us that they were a part of a “wider American culture” that was changing radically and was anxious about its identity. They, like many Jews, wanted to assimilate as they moved from the city to the suburbs. Given this situation, male comedians, argues Epstein, were worried that women comedians could “retard their entrance into American society.”

Within such a cultural milieu it was hard for a woman comic to survive unscathed.

And while men had an easier time assimilating, Jewish women, argues Epstein, were the “new Jews, the unaccepted minority, the people seeking power who were not allowed to gain entrance into society, in this case the society of comedians”(257).

For this reason, Epstein argues that women comics, like Totie Fields and Joan Rivers, were “unable to engage normal comic subjects.” As a result, a woman comedian was “stuck making fun of herself”(257). Totie Fields was the first to do this.

And Joan Rivers “built on Fields’s success.” Her humor, like Fields’ was based on self-deprecation.

However, she was also adept at speaking whatever came to her mind and this helped her to become more independent. However, Epstein argues that it wasn’t until she saw Lenny Bruce perform in 1962 that she became radically independent:

The real turning point for her…was in watching Lenny Bruce perform in 1962. She saw in Bruce a sort of comedy she wanted to perform, a comedy that came from personal, intimate experiences, a direct and honest approach. Rivers was not interested in the political and religious confrontations that came to dominate Bruce’s material, but she was deeply impressed by his delivery style. She transformed his blunt obscenity into softer words such as tramp or slut. She also made a deliberate choice. She went for the large lower middle class. (258)

Epstein characterizes her transition as a “change from self-mockery to self-assertion.” She talked about subjects women never talked about. For a woman to do this was heroic and courageous.

What I find so interesting about Epstein’s reading is that it parallels, in many ways, the reading of David Biale in his book Eros and the Jews. But in Biale’s book, there is a different trajectory which moves from the male “sexual schlemiel” to Lenny Bruce.

Biale, to be sure, gives the schlemiel a fundamental role in the creation of American culture and a new, awkward sexuality which finds its best expression in the work of Woody Allen. He argues that the schlemiel doesn’t simply adapt to American culture; it also creates something new. The sexual schlemiel, with his “comic fumbling,” de-eroticizes “gentile America.” And in doing so, his comic fumbling and “sexual ambivalence infects gentile women and turns them into mirror images of himself: even gentile Americans become ‘Jewish’”(207). With this unique claim and powerful rhetoric (“infests,” “turns into mirror images”), Biale does something no schlemiel theorist has done before: besides noting how women become mirror images of the schlemiel, he also argues that America has become more “Jewish” by virtue of the schlemiel.

Biale goes on to elaborate that there is a “hidden agenda”(207) that goes hand-in-hand with this “mirroring,” which is “to identify American with Jewish culture by generalizing Jewish sexuality and creating a safe, unthreatening space for the shlemiel as American antihero”(207). And this identification illustrates what he means by “harmonizing” Jewish experience with American culture. By being the American anti-hero, Biale is suggesting that the “sexual schlemiel” plays an important role in a new American culture that, in many ways, emulates the anti-hero.

Biale’s choice of words is instructive as it suggests that this “unthreatening space” was prefaced by living in a space of cultural anxiety and a desire to get rid of it. In fact, he notes that in “America a deep insecurity about the Jews position in American culture seems to underlie this instinctive turn tot comedy”(207). Based on this reflection, Biale muses that the distance afforded by comedy may have relieved anxiety by winning over a “potentially hostile gentile audience”(207). For this reason, Biale ventures a hypothesis about how, if Americans can laugh at Jewish sexual neurosis and see such a neurosis as it’s own, then “perhaps the Jew will be accepted as an organic part of the cultural landscape”(207).

However, he notes that since Jews put such neurosis on the screen and in novels, one can argue that they weren’t too anxious so much as slightly anxious. Rather, he argues that they “assumed” that the “sexual schlemiel” was a “legitimate part of American culture”(207) And this prompted them to “generalize Jewish sexuality” by way of the schlemiel.

Biale notes that this generalization of Jewish sexuality by way of the schlemiel was challenged by another one; namely, that of Lenny Bruce. He, “perhaps more than any other comedian, broke with the tradition of the Jew as a sexual schlemiel in order to outrage conventional morality with Jewish eroticism”(216). While Roth and Allen have schlemiels who freely talk about sex, these characters don’t challenge the status quo. As we saw above, they create it by creating an identification between being a schlemiel and being an American.

For Bruce, being Jewish means to “be outside the American mainstream, both verbally (mouths) and erotically (bosoms). It means to identify with what was sexually liberated on the margins of American culture”(217). Biale’s reading makes it clear that the schlemiel – though an anti-hero – is a character that belongs to the American mainstream while Bruce’s anti-schlemiel does not. Bruce, in contrast to the schlemiel, is a part of and edgy and “hip” Jewish culture (217) which “was in as much conflict with Jewish convention as with Christian convention…and for Bruce the former was more sexually liberated than the latter”(217). This suggests a political reading of the schlemiel.

However, Biale notes that while Bruce was going against the American grain he was not a feminist. At the very least, he was “able to imagine a male Jewish counterculture that was subversively erotic”(217). Moreover, Bruce’s kind of comedy – in contrast to the schlemiel’s – taps into a working class ethos. It is Lenny Bruce’s brand of comedy that “captured the bawdy tumult of the Lower East Side culture, from the ribald Yiddish theater to the lurid tales of the Bintel Brief” (219). His work, along with the work of E.L. Doctorow (namely in his novel, The Book of Daniel), evinces a Jewish sexuality that refutes “America’s erotic and political hypocrisy”(220).

Given Biale’s reading, we can say that Rivers also passed from a self-deprecating schlemiel phase to a Lenny Bruce phase. She didn’t simply, as Biale says above, “mirror” the schlemiel. She left this comedic-type behind for a more aggressive kind of comedy. We can also argue that though Bruce was courageous for what he did, perhaps Rivers was even more courageous since she was a woman. And doing what Bruce did, as a woman, was much more difficult.

The question we need to ask is whether Joan Rivers created such a subculture as well. Epstein suggests she did in the sense that she created a space for women comedians to speak and for Jewish women to feel comfortable with being assertive and bold.

And in this, Mel Brooks was spot on. He suggests that she had more courage than all of them. This means that she had more audacity than the Borsht Belt comedians (who he was a part of) and Lenny Bruce. As a woman, she broke more boundaries then they did. And she led the way for comedy to where we are today with comedians like Gilda Radner, Sandra Bernhard, and Sarah Silverman.

We will miss you Joan. You opened doors for women that were closed and you changed the face of comedy. Your legacy lives on and you were…the hardest working woman in showbiz.