In “The Metaphysics” Aristotle distinguishes “perceptions” from “experiences.” Men and animals share the fact that they both have perceptions (sensation plus memory). The first thing that differentiates them from each other is “experience.” Animals can’t have experiences because, Aristotle tells us, they cannot make inferences based on the totality of their perceptions. We do. We infer who we are and what we are by way of our “experiences.” But, for Aristotle, there is a higher mode than experience and that is thinking. When we look for the causes of things, we move beyond inferences. Aristotle acknowledges that scientists may be thinkers but that the greatest thinker is the philosopher since the philosopher looks not for this or that cause so much as the “causes of causes” (that is, the foundation of all things: from which things emerge and return).

But Aristotle makes a concession to experience when he argues that philosophy (always) begins with wonder. However, it ends with wisdom and knowledge. To remain in wonder, for Aristotle, would be to remain in the painful state of ignorance. For him, happiness coincides with leaving wonder behind for knowledge.

To be sure, Aristotle gave birth to a whole line of thinkers who privileged thought over experience (from Descartes and Spinoza to Leibnitz, Kant, and Hegel). Given this tendency toward thought and away from experience, Immanuel Kant – in the 18th century – thought of the novel as a distraction from the “true things.” Since the novel was focused on experience it exposed us to things we could only make inferences about. Dwelling in experience is tantamount with dwelling in confusion, ignorance, and doubt. It would evince – as Aristotle would say – a lower, imperfect form of existence.

In contrast to Kant, Freud argued that we can learn a lot about “who” we are from our past experience. Unlike Kant who thought of literature as a distraction, Freud oftentimes turned to literature and novels to understand what it means to be human. All of our deepest problems and complexes are alluded to in such experiences as we find in dreams and novels. Nonetheless, Freud believed, liked Kant and Aristotle, that we should work our way through such dreams or literary experiences so as to arrive at knowledge. And this knowledge would, so to speak, set one free from this or that condition that hindered our being a reality-adjusted ego. Although the analysis of self was “interminable,” for Freud, it had a goal.

To be sure, Freud would agree that first “experiences,” usually, count for a lot: especially when it comes to one’s identity. A person’s first experiences of a country, a religion, or a culture, especially if they are a “part of it,” can certainly color his or her a) perception of him or herself and b) one’s identifications in this or that geographical, religious, or cultural context.

Oftentimes our experiences are arbitrary; however, sometimes they are primal or “originary.” They can become “first experiences” and may, as the philosopher Martin Heidegger might say, alter how things – and oneself – “appear-in-the-world.” For Heidegger, anxiety was a central mood through which the world was disclosed “as a world” and through which one is disclosed to oneself “as a being-in-the-world” (or as Heidegger would say a “being-thrown,” which suggests a “first experience” of things that was is not familiar with, things one did not know or intend).

In a Freudian sense (vis-à-vis the emergence of repressed materials in dreams), the world can become “uncanny” when buried experiences come to the surface. Freud called this “primary” or “primal” experiences or scenes. In this sense, there can be something shocking or even traumatic about first experiences. And it can certainly be argued that literature is a way of coming to terms with – and perhaps even knowing the “source” of – this shock.

The more schlemiel literature I read, the more I see that sometimes the schlemiel is involved with the literary elaboration of this coming-to-terms with this or that primal experience. What interests me most –as a schlemiel theorist – is to ask what the schlemiel learns or fails to learn – on the one hand – and what we, as readers, learn – on the other. What blindspots do we see vis-à-vis the recollection and assessment made by this or that schlemiel regarding their experiences?

To be sure, working through a character’s “first experiences” may involve bearing witness to something shocking that will make a character appear awkward and comical. The reader may find this schlemiel to be a tragic-comic kind of character since the schlemiel may not know what causes him to err.

In a Heideggarian sense, we may see the schlemiel as a character who is thrown into a situation that he cannot overcome. And, on this note, the schlemiel may come across as a character that is wounded by a traumatic situation that they may or may not know – a situation that he or she may not be able to overcome.

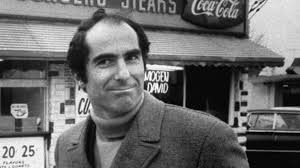

In Gary Shteyngart’s novel Absurdistan, that situation is Jewishness and it is brought out through the main character, Misha’s first “American experience.” Strangely enough, his “first American experience” was shocking and traumatic; it was, according to the narrator, circumcision. Apparently, his first American experience becomes his first Jewish(American) experience. In other words, it alters his Russian-Jewish experience and his perception of Jewishness. And although he is aware of this, he is also blind to how it drives his desire to leave “the Mountain Jews” behind for another, more “multicultural” experience that can only be found in the context and arms of his former Latino-Black lover. This is what I will call the “other” New York; the New York not inhabited by Hasidic Jews – who circumcise him – or “mountain Jews,” who remain in Eastern Europe (in Abusrdistan).

The problem of circumcision is spurred by Misha’s “foolish” love from his father (apparently, a schlemiel/idiotic trait). In one of my previous blog entries on the novel, I pointed out how Misha committed himself to this painful experience out of love for his father (“too much love”). According to the narrator, this love makes Misha into “the idiot” of Dostoevsky’s novel by the same name: Prince Myshkin. We follow Misha as he “foolishly” travels to the circumcision. What happens before, during, and after the circumcision should be duly noted as they trace his trajectory from naivite to an experience that discloses his greatest obstacle, which is branded on his body: his Jewishness. Circumcision affects how he sees himself, America, and Jewishness.

To begin with, his trajectory is spatial and tells us about what he identifies with. Although his first American experience is circumcision, he starts off his American journey in an African-American neighborhood. His observations speak for themselves:

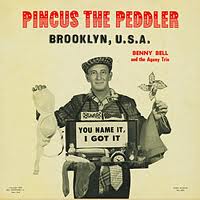

I fell in love with these people at first blush. There was something blighted, equivocal, and downright soviet about the sight of underemployed men and women arranged along endless stretches of broken porch-front and unmowed lawn….The Oblomov inside me has always been fascinated by people who are just about ready to give up on life, and in 1990, Brooklyn was Oblomovian paradise. (19)

The descriptions change, however, when he enters into the Jewish parts of Brooklyn and toward his circumcision. He feels more repulsed by this neighborhood. He doesn’t identify with it though these are his “co-religionists”:

And that (the “Spanish speaking section”) gave way to a promised land of my Jewish co-religionists – men bustling around with entire squirels’ nests on their heads…velvety coats that harbored a precious summer stink…What the hell kind of Jewish woman has six children? (19)

This shift in location is a central motif in this novel which many critics have overlooked. This shift is marked by his circumcision, which leaves him with “his crushed purple bug.” This physical wound is also the limit that separates him from what Hannah Arendt – in her book The Human Condition – would call his “primary birth” and his “secondary birth.” It seems that, for Shteyngart’s Misha’s movement from his primary birth (his “first American experience”) to his secondary birth (which will, later in the novel, be his “first experience” with Rouenna, an African-Latino-American girl he meets, falls in love with, and lives with). But this movement, I will argue, seems to be always plagued not only by his Jewishness but by his wounded penis; his “crushed purple bug.” The proof is in the pudding: if he still thinks about his circumcision and his Jewishness as a burden or wound at the end of the novel, he has not worked through it; if he doesn’t, apparently, he has. Also, we need to ask whether this defines Misha, at the end of the novel, as a schlemiel or a “reality adjusted ego.” Can he leave the wound being for knowledge? Or do we end the novel with a lack of knowledge and a blindspot? Is he, in the end, distracted by his experiences? Or has he found his true, post-Jewish/post-schlemiel self in the “other”?

(In the next blog entry I will give address these questions.)