As a term, the word “schlemiel” (“der schlemihl”) had both negative and positive valances in the 19th, and 20th centuries depending on whether one was in Central or in Eastern Europe and on the intent of the author. While many Zionists and Jewish Enlighteners (Maskilim) in Germany and other German speaking countries often used the term in a negative sense, they sometimes used it in a positive sense. For instance, while Hannah Arendt notes that Rahel Varnhagen (1771-1833) has a negative sense of the term, she argues, with respect to Heinrich Heine (1797-1856) – who occasioned Varnhagen’s Salon in Berlin – that the schlemiel had a positive meaning – since he read it as a figure of the modern poet and the pariah. In Eastern Europe, the use of the term by storied Yiddish writers like I.L. Peretz and Shalom Aleichem were also divergent. While it was often used in a biting satirical sense, the term – as used by Aleichem, Heine, and many folklorists – was also used in an endearing sense. This can also be seen in its everyday usage. One fascinating and telling instances of this usage, which I have come across, can be found in Albert Einstein’s description of one of his closest friends and colleagues, Michele Besso.

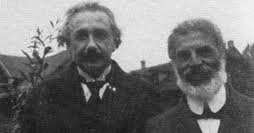

Einstein met Besso when he studied at the Polytechnic Institute in Zurich from 1896-1900. There they became very good friends and confidants. They frequently corresponded with each other from 1903 to 1955. In his exceptional biography on Einstein (Einstein: His Life and Universe), Walter Isaacson notes that Einstein was having a hard time finding work after leaving Zurich. In a letter to his friend (who he later married in 1903 and divorced in 1919) Mileva Maric, Einstein claimed that the reason he couldn’t find a job in German speaking countries was because of anti-Semitism. This led him, according to Isaacson, to find work in Italy and enlist the help of Besso, a Sephardic Jew. Their closeness is illustrated in a letter that Einstein wrote to Besso in which he insists that “nobody else is so close to me, nobody knows me so well, nobody is so kindly disposed to me as you are.”

Isaacson notes that while “Besso had a delightful intellect,” he “lacked focus, drive, and diligence.” Like Einstein, he also had problems in high school. And, to be sure, Einstein saw him as a kind of twin or double. He described Besso as an “awful weakling…who cannot rouse himself to any action or scientific creation, but who has an extraordinarily fine mind whose working, though disorderly, I watch with great delight.” To illustrate this comical kind of disorder, Isaacson retells a schlemiel tale of how, before Einstein caught up with him, Besso had “been asked by his boss to inspect a power station, and he decided to leave the night before to make sure that he arrived on time. But he missed the train, then failed to get there the next day, and finally arrived on the third day.” Einstein recalls how “to his horror (he) realizes that he has forgotten what he’s supposed to do.” So what did he do? “He sent a postcard back to the office asking them to resent his instructions. It was the boss’s assessment that Besso was ‘completely useless and almost unbalanced.”

Echoing these reflections, Einstein, in a letter to Maric, called Besso an “awful schlemiel.” But one should not be distracted by the term “awful,” since Einstein means it in the most endearing sense. He doesn’t correct or chastise his friend for being a schlemiel, as some Jewish German Enlighteners might. Rather, he loves him and his company. He enjoys the time he spent speaking and listening to him. Einstein’s conversations with his dear friend often dipped into science. Isaacson goes so far as to suggest a link between the discovery of the Theory of Telativity and a conversation that they had. He points out how, four years before the discovery, the two had spent “almost four hours talking about science, including the properties of the mysterious ether and the ‘definition of absolute rest.’” To Maric, Einstein noted that Besso is “interested in our research.” Although he “often misses the big picture by worrying about petty considerations” he had connections that are useful.

Einstein’s long standing relationship with Besso and his characterization of him as a schlemiel demonstrate not only a more endearing usage of the term by a German Jew, but also an important idea. Even though a schlemiel may be seen as useless to some (as we see in the story above about Besso missing his train, etc), he may actually be much more useful than any of us could ever imagine. In fact, Besso – a comic scientist of sorts – may even have taken part in the birth of one of the most important ideas of the 20th century. Einstein, in his brilliance, knew this and threw his lot in with the schlemiel. In many ways, Einstein’s close relationship with Besso shows us that he was in many ways a schlemiel himself. His delight in Besso is not contempt; in fact, it shows some kind of affinity. (To be sure, it would be wrong to think of a schlemiel as lacking in intelligence. On that note, take a look at Saul Bellow’s Herzog character.) Perhaps this is one of Einstein’s best kept secrets. Perhaps it was an open secret. After all, Einstein, saw himself as a dreamer and had a penchant for the comical. It all depends on how you read the schlemiel.