“Think snow and see Boca” – Charles Bernstein

Today, the New York Times announced the publication of a new memoir in 2014 by the Jewish-American writer Gary Shteyngart. Shteyngart is well known for his best selling novels The Debutante’s Handbook, Absurdistan, and Super Sad True Story, all of which feature schlemiels as main characters. The title of his new memoir is Little Failure. Regarding his new book, Shteyngart writes:

I’ve finally written a book that isn’t a ribald satire and because it’s actually based on my life, contains almost no sex whatsoever. I’ve lived this troubled life so others don’t have to. Learn from my failure, please.

The last line of Shteyngart’s blurb is of great interest to me. It suggests that the fool is a teacher and has something to transmit to his readers. This suggestion resonates with what I have been blogging.

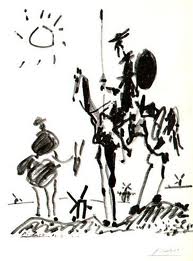

In a recent blog on Walter Benjamin and Don Quixote, I paid close attention to the end of Walter Benjamin’s essay on Kafka where Benjamin foregrounds the relationship between Don Quixote and Sancho Panza. Since Panza followed Don Quixote around and, as a witness and student of the fool, learned from him, this relationship hits on the question of education. In effect, Panza was learning from Quixote’s failure.

In a letter to Gershom Scholem, Benjamin notes that, for Kafka, the fool has wisdom and that the wisdom of the fool, rather than the wisdom of the philosopher, is “the only thing that can help.” However, the question is “whether this can do humanity any good.” This implies that the schlemiel is a teacher. The only question for Benjamin concerns the value of such an education.

Shteyngart, in the final line of his blurb for the New York Times, suggests that he also has something to teach his readers. He sarcastically notes that, like Christ, he has lived a troubled life “so others don’t have.” All we have to do is “learn” from his failure. The structure of this statement and its implication are the same as the structure that exists between Don Quixote and Sancho Panza. Moreover, Benjamin’s reading of Kafka and his appropriation of Sancho Panza and Don Quixote beckon the same questions: What can we learn from failure? What kind of wisdom does a fool have to offer us? Do we simply learn what not to do? Or do we learn something else?

To better understand this, I suggest that we take a look at one of Benjamin’s early reflections on education. In a letter to Gershom Scholem dated September 1917, Benjamin responded to two lines from an essay Scholem had written on Jewish education: “All work whose goal is not to set an example is non-sense.” “If we wish to be serious:…then today, as always, the most profound way – as well as the only way – to influence the souls of future generations is: through example.”

In response to these lines, Benjamin emphatically states that “the concept of example (to say nothing of that of “influence”) should be excluded from the theory of education.”

Benjamin explains himself by pointing out that “the life of the educator does not function indirectly, by setting an example.” What does this mean? For Benjamin, what often happens is that “instruction” is separated from “education.” He argues that “learning has evolved into teaching, in part gradually, but wholly from within.” In other words, teaching is a part of a larger unfolding of tradition.

To be sure, Benjamin claims that the “concept of tradition” is more important than the “concept of the example.” It is more important for a teacher to think of him or herself as a part of a tradition than to think of him or herself as a role model or as the illustration of an idea.

Benjamin sees tradition as the unification of learning and teaching: “I am convinced that tradition is the medium in which the person who is learning continually transforms himself into the person who is teaching, and this applies to the entire range of education.”

Assuming that there is a tradition of the fool (and that Don Quixote is a part of it), Benjamin would see Don Quixote as transmitting it to Sancho Panza. And within this tradition, Panza would continually be transforming himself into Don Quixote (a fool). But there is more. Benjamin insists that “in the tradition everyone is an educator and everyone needs to be educated and everything is education.” In other words, since Benjamin believes in tradition, he insists that all education be reconfigured within the context of tradition; otherwise, education will have no real basis and will become meaningless.

Knowledge, Benjamin avers, is not independent of tradition. It can only be transmitted “for the person who has understood his knowledge as something that has been transmitted.” In this sense, Benjamin believed that if one is to learn from a fool, one must live within the tradition of the fool. To transmit the comic, one must be within the comic tradition.

Moreover, Benjamin believes that a person who situates himself within this tradition, as opposed to someone who rejects tradition (as in the case of modernity), “becomes free in an unprecedented way.” In other words, freedom is not something that one is born with and it is not based on the rejection of tradition; rather, it is something that comes when a person submits him or herself to a tradition.

Benjamin likens tradition and the freedom it offers to the sea and a wave:

Theory is like a surging sea, but the only thing that matters to the wave (understood as a metaphor for the person) is to surrender itself to its motion in such a way that it crests and breaks. This enormous freedom of the breaking wave is education in its actual sense: instruction – tradition becoming visible and free, tradition emerging precipitously like a wave from living substance.

After writing this, Benjamin acknowledges that the source of tradition is religion. He acknowledges that, for this reason, it is “difficult to speak about education.” How can there be a secular or modern notion of tradition? Is this, by definition, impossible? These are questions that were of great concern to Benjamin in many of his essays which look to gauge the effects of technology, media, and mass production on tradition.

Despite the threat of modernity to tradition, Benjamin insists that any form of education which looks to create future students (and this includes all modern forms of education) must find its roots in the religious notion of tradition: “our descendants come from the spirit of God (human beings); like waves, they rise up out of the movement of the spirit.”

Instruction, says Benjamin, is the “nexus of the free union of the old with the new generation.” Instruction, in other words, must bring modernity into a relation with tradition instead of negating it. For Benjamin, the “error” is to think that “our descendents are dependent on us in some fundamental way.” Rather, the proper way of thinking of his or Scholem’s role in education is to think that it all depends “on God and on the language in which, for the sake of some kind of community with our children, we should immerse ourselves.”

Benjamin’s musings prompt an important question for the schlemiel theory: What is the tradition of the schlemiel and who transmitted this tradition to Benjamin? Who was Benjamin’s Sancho Panza? Was it Kafka?

Benjamin suggests this in his letters to Scholem and in his essay on Kafka. Taking Benjamin to his word, we can say that by immersing himself in the tradition of the fool, Benjamin was, as he says, continuously transforming himself into a fool. Moreover, Benjamin was also looking to transmit that tradition to his future readers. Kafka’s work, as an extension of such a tradition, gave Benjamin freedom. It enabled him to break forward like a wave.

This insight, unfortunately, has not been ventured by anyone in Benjamin studies. Benjamin didn’t spell it out. Rather, like any good student of tradition, one must learn it out from the teachers hints and actions. For me, the hints can be found in Benjamin’s obsession with the relationship between Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, a relationship that also fascinated Kafka. Moreover, we can see Benjamin’s submission to the comic tradition in his last letters to Gershom Scholem.

Can we say the same for Gary Shteyngart? Should we take him, as Sancho Panza took Don Quixote, as a teacher? The irony of this tradition is not simply that it is, as Arendt might say, “hidden.” Rather the greater irony is the fact that the tradition of the fool is a modern tradition that, according to Milan Kundera (in a chapter of The Art of the Novel entitled “The Depreciated Legacy of Cervantes”) starts with Cervantes. It starts with the decay of one tradition and the beginning of another, modern comic tradition. According to Kundera, the teaching of this tradition is the teaching of contingency or what I, in my last two posts, would call “empirical consciousness.”

And like any tradition, we learn most from what the teacher does. We can learn more from the teacher’s gestures and actions that we can from his or her content. What I look to do, in my readings of Benjamin, is to pay close attention to the gestures that he has left in his work on Kafka. For Benjamin, one must pay attention to Kafka’s gestures. For they convey something “pre-historic.”

The comic tradition is pre-historic in the sense that it transmits powerlessness to its adherents. All those who learn from failure will eventually fail. Schlemiel education opens the door for that which, in the Jewish tradition, is to come. By learning from the schlemiel’s failure, we prepare for the arrival of what is to come. In this sense, Shteyngart’s memoir, his “little failure” is preparatory. But it belongs to a larger tradition. Our acute awareness of failure, our becoming failures, literally falls within this tradition. So, if we were to see Shteyngart’s memoir (or any of his schlemiels) as an “example” of “what is possible,” we would lose what Benjamin would consider the crux of education: tradition.

But, wait, what does it mean that we are educated with the schlemiel tradition? Is this some kind of joke? Was Sancho Panza the greatest fool of all for taking a fool as his teacher? Did he intentionally distract himself? If so, Immanuel Kant would say that while Quixote was “absent-minded,” Panza was “debilitated.” However, if we take Benjamin seriously, we would have to say that Panza looked to go from being debilitated to becoming absent-minded. To be sure, for Benjamin “tradition is the medium in which the person who is learning continually transforms himself into the person who is teaching, and this applies to the entire range of education.” This kind of transformation, for Kant, would be one of worst sins one could commit against Enlightenment. It is, literally, going backwards – toward the distracted and absent-minded innocence of childhood.

In contrast to this regression, the Jewish tradition has made room for the fool. I have already touched on this in my blog entry on the “Schlemiel as Prophet.” And I will return to it again in the near future since Benjamin, without a doubt, saw something prophetic in Don Quixote’s transmission of foolish tradition to Sancho Panza and, as a matter of course, Benjamin situated himself within that tradition. This tradition is at once Jewish (particular) and not (general). The only question we need to ask is whether or how someone like Gary Shteygart or a blog like Schlemiel Theory is passing the tradition of the fool or the schlemiel on. For, regardless of the decay of this or that tradition in the modern world, comic failure is something that will still be transmitted from generation to generation….