After I learned of Harold Ramis’s death, I spent some time on youtube going through clips of his work. One of the most interesting things I stumbled upon was a talk he gave on Groundhog Day. Ramis begins and ends his reflection on the film with a Jewish joke.

At the outset, he recalls a telephone call from one of the producers on the day of the film’s premier in California. He told Ramis that there are picketers at the film’s opening in Santa Monica. In shock, Ramis asks what they are protesting and the producer tells him: “They aren’t protesting. They are Hasidic Jews walking around with signs saying are you living the same day over and over again!” While he cracks the joke, he has a big smirk on his face.

Following this, Ramis points out how a number of groups identified with the film: Buddhists, people in the Yoga community, Christians, and psychologists. He notes that everyone obviously “projected” something on to the film. However, he adds that “as a Jew, I kept thinking that people finding so much in this movie” and finding something new in it – every time – has much in common with the reading of the Torah:

The Torah is read every year, start at the same place, in the same day…every Jew reads the same form the same day, in the same cycle. The Torah doesn’t change, but every year we read it we change. And every time we read it we read something different. So, the movie doesn’t change.

The punch line is that he denies the comparison after making it and then plays with it: “I’m not comparing Groundhog Day to the Torah; it’s more entertaining. And the Bible was not a good movie…John Huston’s movie.” But the take away is that “there is something in it that can help people to reconsider where they are in life and to question their habitual behaviors.”

This analogy – and the joke that conveys it – is telling. It suggests that Ramis sees the film and the Torah as something that can help us to recognize our mortality and prompt us to change who we are. And we do this by way of reflecting on the story that we see which he suggests has a timeless element to it. What lives on and changes – besides ourselves – is the interpretation of the story. But the point is to make the interpretation.

Reflecting on this, I thought about how, in many ways, Ramis’s films were, for me, like the Torah. I used to watch them over and over again. I was especially fascinated with the juxtaposition of Bill Murray (John) to Harold Ramis (Russell Zisky) in Stripes.

Zisky plays the humble and intelligent American Jew while John plays the ironic and bold American rebel. Zisky and John are both schlemiels. And this is brought to bear on us by way of the fact that they come from a different America than the soldiers they join. They are urban and intellectual; they are ironic and this gives them a vantage point. However, as the film goes on they learn to overcome whatever distance separated them from the others in the platoon. But this distance, though seemingly large, isn’t big.

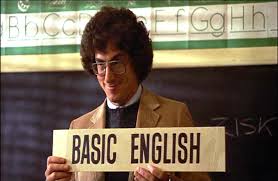

The first scene of the film shows us this fact. Zisky is an educated man who is teaching “Basic English” to Immigrants. We can see that the job is meaningful to him, but it is not allowing him to tap into his full potential.

John is also stumped. Both of them are friends who want, as the Jewish-American writer Bernard Malamud put it, a “new life.” To be sure, Malamud joined Sholem Aleichem, Mendel Mocher Sforim, and other Yiddish writers whose schlemiels all yearned for a “new life.” The question, in all of their novels and stories, was whether such a life was possible or what that new life meant. Moreover, would any of these schlemiels change, fundamentally? Or would they remain schlemiels, still, after the transformation?

When Zisky introduces himself to the platoon in Stripes, he comes across as a pacifist and his words fall flat. None of the other Americans in the room, even John Candy in front of him, can understand or identify with what he is saying or his pledge that he will put himself on the line when they are in danger.

In contrast to Zisky, the American-Jew, is John. His talk is that of a ironic, self-important-cool-populist. The majority of the platoon laughs and smiles when he talks. Everyone can identify with him. He ends with an homage to the leader of the platoon. But the leader sees this all as a lot of talk and, as the film goes out to show, he does all he can do to break John down and make him into a soldier rather than a populist comedian.

As the opening clip shows, the American-Jew and the cool, ironic American are completely different. They are regarded differently by the platoon. That changes over time. But the initial moment gave me a lot to reflect on as a Jew growing up in small town America. My father and mother were both natives of New York City. They were oddballs in my small town. My parents had more in common with Zisky than I did.

For this reason, looking back I can understand why I liked this film so much. I tried to be more like John than Zisky. But in the end, I saw that Zisky was also accepted. But to be accepted, he had to prove that he could put himself on the line for other people in the platoon. And John also had to change. But that change was something that came from the leader of the platoon. The basis for this had to do with making John more humble and respectful.

As a recent Village Voice article points out, this feat of making the American more humble was not realized in films like stripes, however. It was realized in Groundhog Day. According to the author of the article, Ramis established himself by making Slob vs. Snob comedies. While the theme had its power and reflected life in the 80s, it still gave the “white American” slob too much power. The author suggests that this is displaced in Groundhog Day because Bill Murray plays a character who is radically different from characters like John in Stripes. Ramis and Murray, according to the author, figured out that Murray – of Stripes and Ghostbusters – is the “asshole of the age”:

At some point, Ramis and Murray and whoever else seem to have figured out that the Bill Murray of Stripes and Ghostbusters (both co-written by and co-starring Ramis) is the asshole of his age, a self-entitled boomer horndog interested in no perspective other than his own, engaged with no aspect of culture he hasn’t decided he already favors.

For this reason, they created a new Murray character in Stripes who, the author points out, now plays a “snob” rather than a “slob.” The effect of this transformation, is that “he is rightly seen as a privileged dickhead instead of some hypocrisy-exposing hero of the people.” The new lesson, he claims, is that Murray learns that there is more to the world than himself; the world is something you share with others.

I found this article to be interesting since it reads Groundhog Day, as Ramis suggests, by way of a different time. It points out that the film has not changed, but we have. Nonetheless, I wonder how Ramis rather than Murray fits into this reading. Did his character change? And what does this all have to do with Jewishness? And, in all of this, what happened to the schlemiel?

The other day, I blogged on Ramis and pointed out how, in Knocked Up, he played the Jewish father to Seth Rogen. As I noted, the scene I refer to is the scene of tradition and the idea that the son and father encounter is very Jewish. The father is happy to have grandchildren. He is happy to see the future embodied in a grandson. The encounter, so to speak, shows us Zisky years later. Unlike Bill Murray, he hasn’t gone through a fundamental transformation. Ramis, in doing this, shows us that though the Jew may age, his or her humility and priorities remain the same. Zisky isn’t the “asshole of the age.” He just wants to help.

I’d like to end this blog post with a clip from the film Walk Hard where Ramis plays a Hasidic Rabbi who, in this scene, visits, Dewey, the main character, in prison. Dewey is a parody of the American rock star who rises to fame, but ends up in hard times. In an ironic twist, he speaks to him in Yiddish and Dewey replies in kind.

Here’s the rough translation:

Rabbi: Lean closer, I want to talk to you in mother tongue for the guards should not understand what I’m saying.

Dewey: You must be able to do something. I am not yet 21 years old. My whole life is waiting for me.

Rabbi: I think we need to do a retreat.

Dewey: How can we do that?

Rabbi: You must go to a rehab

I recently noted that Woody Allen, in Take the Money and Run, briefly plays a Hasidic Rabbi. But that scene emerges out of a joke: it is a “side effect” of a drug he is asked to take in prison. Here, however, we find something different. This Rabbi is a wise man who looks to help Dewey to live “a new life” the kind of life that he can live if he goes through rehab, that is, a transformation.

The twist, I think, is that the Rabbi initiates the change; he helps Dewey to change his old habits. He helps him to look at himself differently and gives him hope. For me, this is the keynote that Ramis hit at in his talk on Groundhog Day. It articulates what he thinks of the Torah and what he thought of his greatest film. The idea is not simply (or only) that the white American guy realizes that he is an asshole and he can share the world with others, as the author of the Village Voice article suggests; it’s also that the this realization or rather transformative thought is scripted by a Jewish filmmaker and screenwriter named Harold Ramis. He brought his Jewish wisdom to his films and, hopefully, this blog post steps in the direction of better understanding how this was so. To be sure, Ramis’s own words – which I brought out above – suggest that we do so.

After all, the movie may not change, but we do. But the other side of this is that the movie, if read closely, can also prompt us to see who we are and to change our lives. Herein lies the wisdom of a good script and a close reading, something Jews have, for centuries, been familiar. What Ramis has done is to make this structure popular; he has created an offshoot of Jewishness. And he has done it in an American style.