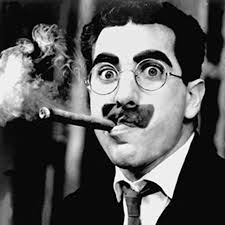

Many a schlemiel-comedian has made his or her livelihood by way of this or that physical gesture (or series of gestures). Oftentimes, these gestures are animations of this or that physical feature. One need only think of the assemblage (to use a word made popular by the philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guittari) of Groucho Marx which included raised painted eyebrows, mustache, a cigar, his odd frames, and his “Jewish” nose. By simply raising his fake eyebrows, widening his eyes, or twitching his cigar, Marx had a punch line.

To be sure, this assemblage has been fetishized and marketed. The animating gesture, so to speak, is missing.

In some cases, this assemblage has become a sign of comedy. Here, in fact, is a book cover by MIT press. The book – The Odd One In – by Alenka Zupancic (the Slovenian philosopher Slajov Zizek’s teacher) espouses a philosophy of comedy.

The cover and the title make an allusion to the Groucho Marx joke about him not wanting to belong to a club that would have him as a member. This classical schlemiel joke is also told by Woody Allen. He, so to speak, also animates it at the beginning of his film Annie Hall (1976) by retelling it – albeit with his own physical mannerisms and gestures that play more on the charming “sexual schlemiel” stereotype.

Although we are clearly aware of how each of these comedians is comically animating their features by way of this or that gesture, what we might miss is the fact that they may also – at times – animating the spaces they are in and even time. One comedian who animates not just himself but also the space and time he occupies is Jerry Lewis.

I was fortunate enough to have recently come across this brilliant insight into Lewis’s character when Steven Shaviro (whose work on film theory, literary criticism, social networking, and philosophy is exceptional – to say the least) apprised me of two recent essays he had written on Jerry Lewis. The second of these two essays addresses Lewis’s relationship to space and time by way of a reading which takes the comedic theory of the Nobel Prize winning late 19th and early 20th century philosopher, Henri Bergson as a counterpoint.

I deeply appreciate Shaviro’s insights since I have also taken Bergson’s Essay on Laughter and his notion of “creative evolution” as a counterpoint to my reading of the schlemiel. What I point out in my work is how, for Bergson (as for many members of the German-Jewish Enlightenment), comedy is purgatory. The act of laughter is based on the act of targeting this or that comic behavior which is “mechanical.” Laughter is a way of saying that such mechanical action must be excluded (purged) from a society which is based on “élan vital” and on a vitalism based on becoming and change. Mechanical repetition evinces the opposite and that’s why, according to Bergson, we laugh at it. We want to become; we don’t want to mechanically repeat.

But in my reading the schlemiel is not to be seen as a character whose behaviors must be excluded; rather, they should be emulated in the sense that they challenge society to change; not the other way around. This is what we see in much Eastern European literature. The “lord of dreams” that Hannah Arendt sees as an obstacle to normality is, in Eastern Europe, closer to truth that those who laugh at him. Her repetitions, therefore, put us into question and this fundamentally challenges Bergson’s reading.

Shaviro’s reading of Jerry Lewis – by way of Henri Bergson – offers another challenge to Bergson while, at the same, opening up a new way of approaching comedy by way of paying more attention to the way a comedian’s gestures affect and animate the space and time around them.

Shaviro takes Jerry Lewis’s film The Patsy (1964) as his starting point. He focuses mainly on the music lesson given to Jerry Lewis by Hans Conreid, the “stuffy, Germanic music teacher.”

In this clip, Lewis appeals to physical gesture by “contorting his body into various grotesque postures.” But, more importantly for Shaviro’s thesis, his gestures affect the space around him since he “ends up either..wrecking the furniture” by touching it or “by sliding down off it and onto the floor.” These caricatures go on and on and end up affecting time and space.

Regarding Bergson, Shaviro points out that Lewis’s gestures are “inelastic” to “an alarming degree.” Lewis is “open to any and every suggestion that reaches him.” His body is like an “electronic transformer” which “amplifies gestures and expressions instead of electric currents.” But, in contrast to Bergson, Shaviro says that these gestures enliven things around the comic and that instead of being outside of a life process – as Bergson suggests comic gestures are – they generate a process. This generation is “visible” and spatial.

Moreover, instead of separating objects in space, Lewis’s gestures of “reciprocal interference” bind things in the room together into a network of oscillating relations. This works, also in terms of time, since instead of crashing objects immediately, Lewis postpones the crash by holding this or that object up before it falls. This creates a “temporal delay” and an excoriating long wait for this or that explosion or crash.

The key, as Shaviro argues, has to do with reading Lewis in terms of “animism” as opposed to the “vitalism” that Bergson thinks about. This animism gives life to dead objects by way of what Shaviro calls “contagion.” But this kind of animism differs from that spoken of by Joseph Campbell and others since it does not “possess” the animator and efface his or her identity. Rather, this animism works like an electric current. And, even the delay of this energy is a part of it’s relay. In fact, the delay of the crash in the above-mentioned scene, according to Shaviro, is an extraction from the horror genre since it works by animating dead bodies; here, objects in the room.

This kind of animation is connected to “cartooning and cinematic animation” which Lewis learned (“inherited”) from the animator Frank Tashlin. As Shaviro notes:

Cartoon animation gives exaggerated life to imaginary and initially inanimate figures; Tashlin and Lewis apply such exaggeration to living bodies themselves, creating an “unnatural” more-than-liveness.

Here is one of Tashlin’s animations from the 1940s. As you can see, inanimate objects like a cage and signs are given life by way of exaggeration. And this, as Shaviro argues, brings together a kind of animism that is opposed to a Bergsonian vitalism (élan vital).

Shaviro ends his essay on Lewis by suggesting that we also look at Karl Marx’s descripion of a table which illustrates “commodity fetishism.” In the example brought by Marx, the product – here a table – comes to life. Marx finds this illustration of the “magical character of commodities” to be grotesque. Playing on Bergson and Marx’s readings, Shaviro makes up a word to illustrate the ideas he is working with; namely a “Marxist-Bergsonian” phenomena which involves the animation of dead objects in space and time by way of comedy.

This thesis is fascinating and it makes the claim that the animism we see in Lewis’s comedy articulates a historical-economic backdrop for his comic-animism. This theory puts an interesting spin on the comedy of Groucho Marx as well since the fetishized glasses, nose, and mustache that are a sign of comedy and of being the “odd one out” have the most power not when they are on this or that person’s face but when they appear in Marx’s films.

Here, for instance, is a great scene that demonstrates how he animates time and space.

I’ll end with a clip from Woody Allen’s Zelig (1983) since it illustrates how Zelig – the human animation – changes vis-à-vis whatever space he is in. And these changes give vitality to everyone around him and create an electric circuit of sorts (much like the spinning of a record). Perhaps this is a product of capitalism, but, as Irving Howe argues (in this very film), it can also be read as a product of assimilation. Regardless, Shaviro’s suggestion about Lewis could also be applied to Allen. Ultimately, these animated comic gestures would be nothing without animation but, as a part of the package, Jewish identity is (as Jacques Derrida would say vis-à-vis the text and deconstruction) supplemented by animation: