In The Schlemiel as Metaphor: Studies in Yiddish and Jewish American Literature, Sanford Pinsker devotes an entire chapter to the work of Phillip Roth. Well, that’s not entirely true. Although the chapter is dedicated to Phillip Roth, the majority of the chapter is on Roth’s most popular and controversial novel, Portnoy’s Complaint. For Pinsker, the other two novels that are mentioned in the last part of the chapter – The Ghost Writer and Counterlife – do not so much illustrate the schlemiel as put forth a new type of postmodern novel that emerged after Portnoy’s Complaint. Pinsker suggests that these novels were not so much about the schlemiel as an attempt to leave the schlemiel behind for the novel within the novel and writing as such.

One of the most interesting elements of Pinsker’s treatment of Portnoy’s Complaint is the evidence he marshals to prove that Portnoy is a schlemiel. Pinsker stages his argument by pointing out Portnoy’s favorite pastimes: masturbation and mouthing off. To be sure, Portnoy violates all decorum by speaking in detail about his masturbation and mentioning all the places he has left his semen. Ruth Wisse and Sidrah DeKoven Ezrahi would argue that this “mouthing off” is an important trait of the schlemiel. Portnoy’s words give him, as Wisse would say, an “ironic victory.” But, for Pinsker, this isn’t the only thing that makes Portnoy a schlemiel.

Rather, the key trait of the schlemiel can be found in Portnoy’s memory of failure: “What he remembers most, however, about these masturbatory binges are his darkly comic failures. In this regard, none is more spectacular that his disastrous episode with Bubbles Girardi.”

As Pinsker recounts, Bubbles made a deal with Portnoy’s friend Smolka to “jerk off one of his friends.” However, there are two conditions: 1) the individual will have to leave his pants on and 2) she will “count fifty strokes” and no more. Portnoy is elected to receive the “prize” but “the result is comic schlemiel hood of the first water”(149).

What Pinsker finds comic is that Portnoy is brought right to climax, but Bubbles stops at 50 strokes. Portnoy cries out:

JUST ONE MORE! I BEG OF YOU! TWO MORE! PLEASE! N-O!”

Portnoy reflects on his failure and decides that he’ll have to finish the job whereupon he cums in his eye: “I reach down and grab it, and POW! Only right in my eye.”

The greatest insights in Pinsker’s book on the schlemiel – and in his chapter on Roth – follow upon this passage.

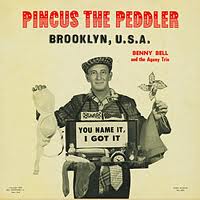

Pinsker notes that “Portnoy’s sexual antics are the stuff of which Borsht Belt stand-up is made, but as he keeps on insisting, this is no Jewish joke, no shpritz (machine gun spray of comic material”(150).

And this is the ironic denial that makes him a schlemiel. Roth is doing Schlemiel Stand Up. Unlike Lawrence or Joyce, Pinsker tells us that Roth doesn’t take his failures with a “high seriousness”(150). Rather, Roth is a tumbler (an acrobat of sorts): “Roth reduces to the anxious flip. The cunning of history is to blame here; when Portnoy shouts “LET’S PUT THE ID BACK IN THE YID! The effect dovetails a domesticated Freudianism into the jazzy stuff of popular culture”(150).

What does Pinsker mean by this “jazzy stuff of popular culture?” Pinsker notes that what Roth has popularized and made comic is the stuff of tragedy: guilt. And who else but Franz Kafka is the teacher of how to make guilt a comic affair. To be sure, Roth said this in his book Reading Myself and Others (1975). There, he notes that he got his stand-up routine from a sit-down comic named Franz Kafka: “I was strongly influenced by a sit-down comic named Franz Kafka and a very funny bit he does called ‘The Metamorphosis’… Not until I got hold of guilt, you see, as a comic idea, did I begin to feel myself lifting free and clear of my last book (Portnoy’s Complaint) and my old concerns”(150).

Pinsker uses this line as evidence that Roth may have come from Kafka and he may practice the schlemiel, but he wants to lift himself “free and clear” of this character. For Pinsker, all of Roth’s future books were more mature while Portnoy’s Complaint was all about “enjoying being bad.” Portnoy’s kvetch, his complaint, and his enjoyment of being bad differ, Pinsker tells us, from Walt Whitman’s “barbaric yawp” since Portnoy is not the man in the sense that Whitman portrayed himself to be. He is afflicted by his own misfortunes and guilt. Whitman is guilt free, Roth is not. Here, Pinsker suggests that Portnoy’s mouthing off doesn’t change his reality. He is still caught up in his masturbatory dreams and his guilt, which he can’t seem to escape. His stand-up comedy doesn’t make a difference. It seems, more or less, like impotent rage.

What Pinsker overlooks, however, is the fact that Portnoy’s greatest humiliation – his greatest and final complaint – comes at the end of the book with Naomi, the Sabra (native Israeli). This time, he gets to sleep with a woman. But before he does, he comes to realize that he is no match for her. This dialogue brings out the crux of the new Jewish-American schlemiel who lives in the shadow of the Sabra.

Naomi deftly describes the difference in her characterization of Portnoy’s stand-up routine in which self-ridicule is the most prominent feature:

You seem to take some pleasure, some pride, in making yourself the butt of your own peculiar sense of humor. I don’t believe you actually want to improve your life. Everything this somehow always twisted, some way or another, to come out ‘funny’ All day long the same thing. In some little way or other, everything is ironical, or self-deprecating. (264)

After Naomi goes on to discuss how powerlessness got Jews nowhere, Portnoy says, flat out: “Wonderful. Now let’s fuck.”

In response, Naomi calls him “disgusting” and then they engage in a name-calling match in which Naomi puts the nail in the coffin by calling him a schlemiel. Notice that in the following, “Schlemiel!” (in italics) is the final word:

“Right! You’re beginning to get the point, gallant Sabra! You go be righteous in the mountains, okay? You go be a model for mankind! Fucking Hebrew saint!” “Mr. Portnoy, “ she said…”You are nothing but a self-hating Jew.” “Ah, but Naomi, maybe that’s the best kind.” “Coward!” “Tomboy.” “Schlemiel!” (265)

Portnoy, cursing under his breath says, “I’ll show her who’s the schlemiel!” But he fails, sexually. He’s impotent.

As you can see from these lines, Naomi has the last word. And that word is schlemiel. She is strong and he, a man, is weak. What we have here with Naomi is the new, Israeli Jew (which scholars like Daniel Boyarin, David Biale, and others discuss at length). In the face of Naomi, the Sabra, all Portnoy has for power is his wittiness and vulgarity. But the irony is obvious. Roth is showing that Portnoy’s words are no substitute for her physical power. Rather, his wittiness differs and competes with her power. And, like any schlemiel it loses in the end. What remains in the aftermath of all his verbal acrobatics is his failure. (The acrobatics metaphor which I mentioned in my last blog on Beckett and Federman fits well here.)

Sidrah DeKoven Ezrahi interprets the meaning of Portnoy’s failure in Booking Passage: Exile and Homecoming in the Jewish Imagination. Ezrahi notes that Portnoy explicitly confesses to his loss when he sings a self-depricating song, which he has created for this specific situation of failure: “Im-po-tent in Israel, da, da, da”(226). Ezrahi’s interpretation of this moment of failure is telling.

On the one hand, Ezrahi says that the novel demarcates the “very moment when the schlemiel as cultural hero is superceded by what the critics of Zionism call the “tough Jew,” when “images of Jewish wimps and nerds are being supplanted by those of the hardy, bronzed kibbitznik, the Israeli paratrooper, and the Mossad agent.” On the other hand, she notes that in Roth’s later novel Operation Shylock the schlemiel becomes a competitor: “What has happened to turn powerlessness into a competing cultural claim and Diaspora into the most authentic and secure form of Jewish existence?”(226).

The lines that follow this question, however, demonstrate that Ezrahi doesn’t believe Roth’s project has left the schlemiel behind. The claims he makes in Operation Shylock are still based on powerlessness: “Once again Roth’s hero is defeated in Israel, but this time in a battle, fought with weapons – the pen and the sword – no less phallic but more consequential. Israel has become the place where Reality writ large has the same affect on the psyche as Naomi did on the libido”(226-7).

In other words, Roth’s characters are still schlemiels but now Exile, “redefined as “Diaspora,” is no longer limited to the realm of therapy (as it was for Portnoy) but extends to the much larger realm of fiction.”

Fiction and not the libido becomes the resevoir of the dream and fantasy while Isreal becomes Reality (Israel IS-REAL) or the reality principle. This contrast shows that, for Ezrahi, the schlemiel’s battle is not simply psychological as it was with Naomi. Portnoy’s problem may be psychological, but the narrator and main character of Operation Shylock – whose names all happen to be Phillip Roth – have a problem with Israel. In other words, their Jewish identity is ruptured by its very existence.

But, to be sure, we also see that this problem exists in Portnoy as well. His problem is not merely psychological. After all, he tries to call Naomi names so as to show he is more powerful, but it is to no effect. Reading Ezrahi’s take on Roth, one cannot help but think that Roth is fully aware that he is on the side of the dream; and the side of the dream, as even Roth suggests, will always be the side of guilt and failure.

If Roth takes his task from Kafka, as Pinsker tells us, Ezrahi’s observation is very telling. Roth admits that he saw Kafka as a “sit-down” comedian who took the tragic notes out of guilt by making guilt comical. As Pinsker argued, Roth believed that by writing he would eventually be done with guilt and the schlemiel. But as Ezrahi argues, this project, inevitably failed. Why?

For Ezrahi, this project to leave schlemiel-hood can never be completed since there is a competing claim; namely, the claim of reality (the claim of Israel). And this claim demonstrates that the real basis for the schlemiel, for Ezrahi, is the difference between dreams and reality (or as she puts it, Exile and Homecoming). For her, language, without a land, provides (and has, traditionally, provided) nourishment for the exiled Jew. The schlemiel’s words, as Wisse would argue, give people a sense of dignity in the face of failure. But, as Ezrahi suggests, fiction, like the schlemiel, can’t stop dreaming. Given these premises, I would suggest that Ezrahi can argue that Roth is not simply a schlemiel in the sense that he doesn’t know what is going on in reality. No. He is a guilty schlemiel. We see this above, in the citations from Portnoy’s Complaint. He, so to speak, enjoys his symptom.

Ezrahi suggests that in Operation Shylock Roth makes it explicit that he may fight with Israel but, ultimately, he will always be a comic failure. His identity, as a Jewish-American writer will be ruptured. He knows that his homeland is in a text while being cognizant that Israel is now a reality. Ezrahi suggests that he knows that he has refused history in the name of fiction. But do Jewish-American writers share this awareness? Are they, like Kafka and other pre-Israel schlemiels, not able to properly enter history? To be sure, as a result of this failure, which they were not fully responsible for, Ezrahi tells us that they had to live in a “substitute” land with a “substitute” sovereignty. Today, Ezrahi argues, one no longer has to do this. A Jew can go home and “recover” their history. But writers like Roth consciously opt not to. And this opting-not-to constitutes their comical identity. So, today, the schlemiel and its comic relationship with guilt remains but now it has a different basis.

What amazes me most about all of this is that what Roth and Ezrahi both seem to be saying is that to be an American Jew –and to resort to a constructed identity, fiction, and dreams – is to be a schlemiel. Ezrahi calls this a “diasporic privilege.” Based on this logic, one can say that living an ironic, schlemiel-like existence is a “guilty” pleasure that is had at the expense of returning to the land. American Jews, as schlemiels, enjoy their symptom. Now, being a schlemiel has a price; but before Israel was Real (for many before 1967), being a schlemiel was, as Ruth Wisse argues, necessary for Jewish survival.

For Ezrahi, Jews are forced to answer a question: What side are you on? On the side of Portnoy or Naomi the Sabra? One can brazenly be a schlemiel and deny any guilt, but at what price? This, I think, is one of the main questions Ezrahi wants American-Jews to ponder. Unfortunately, no scholar I have met who has read Ezrahi has figured it out. For some strange reason, they miss this question and, instead, think Ezrahi is praising Diaspora. This misreading, though unfortunate, is telling.

I won’t make this misreading. I’m here to ask this question and to reflect on what it means. Should I read Roth as she does – in terms of his comic acknowledgment of a guilt that is based on saying no to Israel? Or should I consider myself to be a “New Jew” (see David Shneer and Caryn Aviv’s book New Jews: The End of Diaspora, who, according to these authors, is not bound by the distinction of Diaspora and Homecoming)?

What better time to pose this question than today on the 65th Anniversary of Israel’s founding in 1948? Ezrahi has every right to ask us to ponder such guilt since she lives in Israel and knows full well that there is a difference between being Jewish in Israel and being Jewish in America. I do not see it from her perspective.

I read and write about the schlemiel, but with a difference. As an American-Jew, I understand that with Israel’s existence, my enjoyment of the schlemiel can be thought of as a guilty pleasure. And I clearly understand that her reading hinges on Jewish history. If an American Jew thinks he or she is beyond the dream of having a land of his or her own, he or she is thinking ahistorically. Though this is possible, and happens often enough (since, unlike Phillip Roth, many Jews lack an acute sense of what is at stake with Israel or how they are a part of a long history of Exile), one needs to ask oneself what is at stake if we totally lose our “Jewish guilt” which, today, is not tied to anything primordial but, quite simply, to Israel. Can a Jew simply leave the schlemiel behind, which, for Ezrahi, would suggest that one leaves Israel and history behind? Or are Jewish American novelists – like Shalom Auslander or Nathan Englander (to name only two) – willing to embrace this character and its ironic relationship with the Isreal? Will the schlemiel remain, regardless of what we do, since Israel and America will most likely remain the two primary places where Jews live and dream?

These questions should trouble American Jews and be so troubling as to make us complain a little and realize the situation we are faced with. Perhaps, for American Jews -in general – and Jewish-American writers – in particular -Israel is or will be the Final Complaint (as it was for Portnoy and for the author of Operation Shylock)?