Near the end of his life, Leslie Fiedler, the celebrated (or is it notorious – Irving Howe – one of the greatest voices in post-WWII literary criticism – thought of Fiedler as a charlatan) Jewish-American literary critic decided to write a book that spoke to his guilt for having been complicit in power. In What Was Literature: Class Culture and Mass Society, he makes claims about American culture, authorship, and criticism that suggest that in order to get where you are you have to throw someone under the bus.

As Fiedler explains, a whole generation of writers amassed wealth by profiting off of losers. This is not simply a fault that can be found in human nature – it has to do with the nature of American culture. And, as an American literary critic-slash-writer nearing the end of his life, he admits his guilt. The meaning of this guilt is telling since it suggests that – in not being alone – many American writers (or filmmakers – think of Seth Rogen, Judd Apatow, Woody Allen, Adam Sandler, Ben Stiller, etc) are also profiting off of losers. But, in his estimation, he is better than most because he is willing to admit it.

The first line of his book admits to a kind of guilt, but it is displaced because, although it seems personal, it is really academic; namely, the distinction between high and low culture:

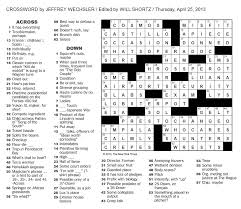

After more than forty years in the classroom talking about books, I find myself asking whether the profession I practice does not help perpetuate an unfortunate distinction, a separation of song and story into High Literature and low or as some prefer to say, into literature proper and or sub- or para-literature.

But when the reader juxtaposes this sentence to the title of the chapter “Who Was Leslie A. Fiedler,” one will see that his guilt is in question. If we are looking into who Leslie Fiedler “was” – vis-à-vis his view on the high-low literary distinction – what can we say about who he “is”?

Based on this first sentence and its relationship to the title, the obvious assumption made by the reader is that the Leslie Fiedler of the past made distinctions between high and low literature while the present Leslie Fiedler does not.

Fiedler admits that – as a literary critic and teacher of “my generation” – it is “shameful or regressive to respond similarly” to low literature as one would to high literature. Yet, he says, that is what his “generation of literary critics and teachers of English was expected to do.” And when he started putting the two on the same level, he felt guilty. Although it sounds sincere, there is something odd about his testimony.

Fiedler argues that, initially, he was (since the age of seven) a writer not a literary critic. And instead of accepting his pieces of fiction, the people he sent material to wanted literary criticism:

I am not sure even now what prompted them to make such requests beyond a vague sense of guilt at having to say no (to his fictional pieces) over and over again to one so desperately in need of some kind of yes. But in any case, I did not pass up the chance. (14)

In other words, Fiedler was desperate. He wanted “some kind of yes” and he found that being a literary critic, which, for him, meant tossing his standards to the wayside, was fine. He didn’t mind lying about what he really felt, and he became…someone else. The new Leslie Fiedler, in other words, is a liar. But, for him, since one needs “some kind of yes”from the American public, one must become a liar

But, as Fiedler reveals, there is more to the story of duplicity in America. It does some good. He, like many, did it for the money. And the contracts he agreed to made him into a public figure who, from time to time, appeared on TV. But these appearances were, for him, more relevant because they “return” to the “’archaic’ public lecture, the Chautauqua”(19). This gave him a “connection” to a non-academic audience which he felt was more important than the small audience he had in this or that university English course or academic lecture.

Somehow television came closer to giving me the sense of connection with a responsive nonacademic audience that I had experienced for the first time when someone in a heterogeneous group of listeners (it was in a park, as I recall, on the South Side of Chicago) screamed, “Now you’re preachin’, brother. Go right on preachin’.”(19)

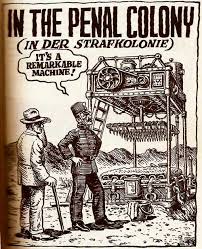

But, says Feidler, television “ran out for him” and he admits that he was a “victim of vestigial elitism.” Nonetheless, he had not “escaped ‘show biz’ and went on a lecture circuit. While this was going on, he had, by 1963, written a “novel called The Second Stone.” In the novel, Fiedler casts the main character as “an expatriate American loser, a writer who does not write”(20). This “American Loser” disrupts a “World Congress on Love held in Rome under American auspices” because the main character becomes the love infatuation of the “wife of a theologian-organizer.” He situates this character amidst “the deliberations of the assembled critics, poets, shrinks, and gurus are drowned out by the shouts of demonstrators, convinced by the Italian Communist Party that the whole thing is a CIA plot”(20).

Fiedler’s decision to cast himself as the “American loser” – as a “writer who does not write” – is telling because he sees this trend as disclosing a kind of American duplicity. In America, writes Fiedler, there is a belief that the public feels powerful and guilty for the death of great authors like Poe and Fitzgerald. It wasn’t booze that killed them. According to the American public, it was power. The mixture of power and guilt is a “potent emotional mix for all true Americans”(31). When he writes this line, Fiedler includes himself as a “true American.” But the guilt he has, as a critic and a writer, is profiting off of their failure:

It is, for instance, Mark Twain’s final loneliness and melancholia (that) we prefer to dwell on, or his many failures along the way. Yet, though Twain went bankrupt as often as any other capitalist entrepreneur in the Gilded Age, at the end he was able to support a splendiferous house and a set of expensive bad habits. (31)

The irony, writer Fiedler, is that Twain’s fortune was “based on the continuing success of Huckleberry Finn, which is to say, the classic version of the American anti-success story”(31). Twain’s life as a child was the opposite of Tom Sawyer’s. He “would not allow Tom” to “grow up,” while he, himself, did. Twain “stayed home.” He didn’t go on a journey. In other words, Twain profited off of the American loser and in doing so he lied. This, suggests Fiedler, is the price one must pay if one is to be a popular writer or critic.

Fiedler goes even farther and suggests this was the case for a whole generation of Jewish American writers who, as American losers, a writer like Saul Bellow profited off in his book Humboldt’s Gift. According to Fiedler, the poete maudit is “reborn this time as a failed New York intellectual – a super-articulate, self-defeating Luftmensch who has died abandoned and penniless before the action of the novel begins”(32).

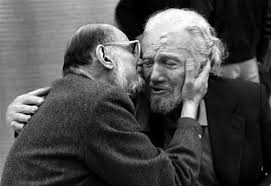

Citing other critics of Bellow’s book, Fiedler notes that the model of the book was Delmore Schwartz, “who had indeed come to a shabby end”(32). For Fiedler, Schwartz is:

The portrait not of any single individual but of a whole generation of Jewish-American losers: including, surely, Bellow’s one-time guru and lifelong friend, Isaac Rosenfeld, also dead before reaching forty, his handful of stories and essays remembered by a shrinking coterie of aging admirers; and perhaps Lenny Bruce as well, that hipster and stand-up comedian who O.D.’d in 1966. Reading Humboldt’s fate, I cannot, in any case, help thinking of all those mad, bright, young Jewish-Americans, still caught up in the obsolescent myth of the Artist as Victim, and dead before they had lived long enough to realize, like Bellow, that in prosperous America it was no longer necessary to end as a Beautiful Loser. (32)

Fiedler argues that the ultimate beneficiary of the loser in Bellow’s book is the narrator, Charlie Citrine (the “not-so-beautiful Winner”). He is the “real hero,” not Humbolt (32). He feels a kind of power for surviving the character’s death; however, his “own survival is an occasion for guilt – the guilt we have long been trained to think of as the inevitable accompaniment of making it”(33). By writing this, Feidler suggest that he has also felt this power and guilt. He is a survivor – a “not-so-beautiful Winner” – who has taken advantage of the American loser, too.

One way of assuaging this guilt, according to Fiedler, is by believing that the loser died so that you could win. And their death leaves us with a “heritage not empty regrets but a salable story: his story once, our story now, the book we are reading”(33).

The story of the American loser can – “if properly exploited” – be made into a film or earn an author (such as Bellow) a Nobel Prize. The survivor can pay the bills. But Fiedler’s portrayal of the survivor and winner is sad and discloses his guilt which he is trying to hide:

And if we weep a little, remembering those others whom we loved and betrayed and by whose death we profited, we can (as the old saying has it) cry all the way to the bank. (33)

All ends on this note because this is not who Fiedler (or perhaps any American literary critic) “was” so much as who he has become. In order to make it, he, like Saul Bellow or Mark Twain, had to profit on the American loser. Both American and Jewish American literature and their power – in his estimation – are guilty of this. The implication is that Jewish American – as much as American literature – needs its losers, Luftmensches, and schlemiels if it is to live on and tell the tale, but this survival is a kind of betrayal.