In a brilliant essay on literature and music, Milan Kundera argues that the “history of literature” can be understood in terms of “two halves.” The first half of literature is comic. He associates it with Cervantes’ Don Quixote and Francois Rabelais’ Gargantuan and Pantagruel. In contrast, the second half of literature is realistic and historical. Kundera associates it with Emile Zola, Walter Scott, and Honore de Balzac. The two are at odds: “the chasm between the aesthetics of these two halves makes for a multitude of misunderstandings.” Citing Vladmir Nabokov’s reading of Cervantes, Kundera notes how, for the realist, Don Quixote is “overvalued, naïve, repetitive, and full of unbearable, and implausible cruelty….poor Sancho, moving along from one drubbing to another, loses all his teeth at least five times”(58, Testaments Betrayed). Kundera takes Nabakov to task by pointing out that while “Sancho loses too many teeth…we are not in the world of Zola, where some cruel act, described precisely and in detail, becomes the accurate document of social reality; with Cervantes we are in a world created by the magic spells of the storyteller who invents, who exaggerates, and how is carried away with his fantasies, his excesses….Cervantes’ great founding work was alive with the nonserious, a spirit that was later made incomprehensible by the Romantic aesthetic of the second half, by its demand for plausibility”(59). By pointing out this chasm and the misunderstanding that comes out of it, Kundera suggests the possibility of bridging it with a new kind of novel. The model, for Kundera, is Kafka’s Amerika. Kundera calls it a “literature made of literature.” It manages, as Kafka envisioned, to draw on and subvert Charles Dickens’ David Copperfield by revising certain motifs in a comical manner.

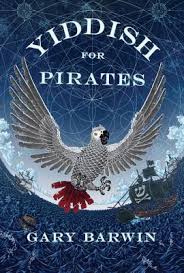

“Literature made of literature” is a good phrase to use to describe what, in the Jewish tradition, is called Midrash and it aptly describes Gary Barwin’s newest novel, Yiddish for Pirates. To be sure, the name of the novel suggests that pirating is a central motif of the novel. But since it is more in a comical than in a realistic sense and because the narrator of the story, after all, is a parrot, I would call the novel an act of parroting. But with a difference. The parrot doesn’t merely take for this or that language or tradition and repeat it. The parrot is a storyteller and his job, like that of the Torah, is to convey not just a memory but a moral teaching.

Throughout the novel, we find parroting at work in the plot, characters, and humor. By way of such comical parroting, Barwin is able to bridge the gap between the comic novel and the realistic novel. What is most fascinating is the fact that the subject of the realistic novel, which he interpolates into the comic novel, is something that has never been addressed by way of a comical postmodern Canadian novel: the Jewish experience of the Inquisition, living as Marranos, and the journey to the New World.

Because of its comical elements, its focus on Yiddishkeit, and its nuanced reflections on spatial and temporal displacements, Yiddish for Pirates suggests a literary experience that can be found in the Torah and modernist fiction. It gives the reader an opportunity to experience something akin to an embodied comical faith. One can experience this through a reading that cares for a plot and characters whose relationships over time and space – which are “pirated” from biblical and historical sources – can be the source suffering, hope, and comical joy. The irony is that this kind of faith requires a good sense of humor coupled with a strong sense of Jewish history and its vicissitudes. One has to, to play on the novel and use a metaphor for embodiment, know how to ride the waves.

Faith, Time, and Learning

In a 1956 interview with William Faulkner, the interviewer, Jean Stein, asked Faulkner about who he thought the greatest writers of his youth were. He replied that Thomas Mann and James Joyce were. But he added that one must read them “as the illiterate Baptist preacher approaches the Old Testament: with faith.” The fact that Faulkner saw the link between literature and the “Old Testament” rather than the “new” is telling. What is the link between modernist literature (as we find in Joyce and Mann) and the Torah (“old Testament”)?

Modernist fiction is very interested in the relationship of fragmented time to plot, character, and narration. The characters and the perspectives of the narrators are limited. Likewise, faith, in the Torah, has a lot to do with fragmented time and limited perspective. Characters and readers are rooted in time and its jagged temporal unfolding. As the Jewish philosopher Franz Rosenzweig noted in his opus, The Star of Redemption, Judaism consists of three temporal relations that are totally distinct from each other: Creation (Past), Revelation (Present), and Redemption (Future). Time is, for this reason, measured in terms of the process that the Jewish people have to go through before the arrival of Redemption. And this process need not be linear it can take on a number of different rhythms.

But time just doesn’t happen. According to Rosenzweig this temporal process includes another three other points of relation: God, Man, and World. Time, in other words, unfolds in terms of man’s relationship with God, God’s relationship with the world, man’s relationship to the world, etc. Harold Bloom, in his book Agon: Towards a Theory of Revision, helps us to better understand what this means. He notes that the unfolding of time has, for the Bible (Torah), a moral and educative meaning. Through time, the Biblical character learns about God, the world, and him or herself: “Because learning is a process in time…The thought-form of the Hebrew Bible depends upon a movement in the fullness of time, a movement in which moral learning can take place”(59). To Bloom’s observations, I would add that this kind of “moral learning” is also connected to two other elements found throughout the Torah: 1) a movement from place to place (the process is, so to speak, a journey) and 2) the process of living through different relationships. All of these elements suggest that Judaism is temporal, relational, and embodied. Judaism is not a religion dominated by a spirituality that transcends the world, history, and humanity. It is a religion that is primarily relational.

The same can be said for Barwin’s novel. The irony is that the main relationship in the novel is comical: it is between a parrot and a human being. And, like many a Kafka story, the reader, at some point, is startled to discover that their narrator is an animal. It is the animal who is the cipher of tradition and through the animal the relationship and the story lives on. But unlike many of Kafka’s animals, this one tells jokes. Perhaps, by trusting the comical animal narrator, one has, in a sense, a kind of comical faith that “parrots” the faith that is found in the Bible?

Moishe and Aharon: Pre-Modernity, History, and the Model Relationship

Instead of revising modern history, Yiddish for Pirates decides to focus on the relationship between Jews and four pre-modern worlds: the world of the Eastern European shtetl (in which Yiddish was the lingua franca), the world of the Inquisition, the world of Pirates at Sea, and the world of the frontier (which took Columbus on a search for the New World and others for the “fountain of youth”). Barwin’s decision to focus on this time is timely since it suggests, with each world, a different relationship with history that needs to be given a new kind of figuration.

At the very outset, Yiddish for Pirates asks the reader to take the relationship between a 500-year-old Parrot narrator named Aharon and his companion (the hero of the novel) Moshe to heart. Drawing on and revising the Biblical relationship of Moses to Aaron, the novel plays on the Biblical text that notes how Moses had a speech impediment and needed his brother to speak for him. The irony is that while Moshe remains a dramatic and heroic character, the narrator is comedic and anti-heroic. The juxtaposition of the two makes for a rich text and gives the reader a lot to think about. And it is through their relationship – in a Rosenzweigian and Bloomian sense – that time unfolds and learning happens.

The first relationship of the novel is established with the reader and it is at once comical and serious. Aharon says hello to the reader and one can hear a voice that is at once comical, very intelligent, and Yiddish. It also suggests a voice that knows too much, remembers too much. And in so doing bridges the chasm between the comic and the realistic/historical.

Hello. Howaya? Feh. You think those are the only words I know? Boychick, you don’t know from nothing. You ain’t seen knowing. I may be meshugeh crazy, but I know from words. You think I’m a fool shmeggege? I’m all words.

Hello? If you want the story of a life, don’t wait for your alter kaker old gramps over there to wake up. Maybe he’ll never wake. But me? Listen to my words. They tell some story. Because I remember. Sometimes too much, but I remember.

To be sure, the comic voice gives the reader a way to identify with finitude that is not tragic. It is familiar and intimate in ways that family members are with each other. (The novel suggests a familial relation in the epigraph: “For the whole misphocheh (family), fore and aft.) And this is the voice that accompanies not just the reader but Moses on his journey from Europe to the New World.

Barwin, thoughout the novel, also stresses the burden of memory and the responsibility of telling the tale. But this is, like many a human endeavor, hard to accomplish. We try to remember. But we often forget. As Aharon jokingly notes, “I speak many language and I’m fluent in both remembering and forgetting.” But, in truth, the pain of losing the memory of Moishe, for the narrating parrot, is great since he takes Moishe as a loving companion. It’s his memory and the story itself, however, that distract and have a life of its own: “The horizon is always the story, and as soon as we get there, it’s somewhere else.” Displacement is at work everywhere. It is also the substance of exile. Rather than take this in a tragic sense, Aharon conveys displacement in a tragic-comic sense. Through his humor, he makes the best out of exile. He embodies it through his humor.

For instance, in a scene where a battle is described, Aharon injects humor so as to avoid too much pathos and drama. Notice the punch line: “It wasn’t much of a battle…There was a the customary disemboweling, cutting off of noses, hands, and of shmekles”(7).

Moishe is portrayed as leaving the shtetl in Eastern Europe for the high seas and adventure. At the outset he’s depicted as a schlemiel. He doesn’t want to fight on Shabbos. And this, at the outset of the novels four parts (Air, Fire, Sea, and Land), suggests his initial comic condition as a luftmensch (a man who lives, comically, on air): “A boychik with big ideas, his kop – his head – bigger than his body”(11). The body is a “scrawny map of himself.” As the novel progresses, Moishe matures and his body becomes strong. He goes from a schlemiel to a mensch.

But Aharon, the parrot-narrator, remains a comical figure throughout. And for good reason. As Kundera notes, while the playfulness of the narrator – which we see in Cervantes and Kafka – gives freedom to the modern novel, the realistic narrator is bound to detail and pathos. Aharon’s comedic view of himself and things – which is mediated through his constant self-deprecation and use of Yiddish – gives him a kind of freedom and also makes him into an endearing schlemiel of sorts. He doesn’t age, while Moishe does. He may be “grey” and old but he’s young because of his comic demeanor.

An important aspect of the novel is the coupling of humor with friendship. It is more interesting than the journeys through the Spanish Inquisiton and the journey to the New World that are embarked on in the novel. It survives all of the realistically depicted battles, acts of revenge, and exploits that are found throughout the novel. And, in many ways, it – is what keeps Yiddishkeit alive. After all, the parrot knows more Yiddish than anyone, even Moishe.

Aharon’s epiphany at the beginning of the novel and his reflection on loss at the end demonstrate this powerful motif that parrots the Torah and its stress on the power of relationship and family. Barwin’s poetic cadences bring the importance of language to this relationship and its embodiment. It shows us how time unfolds through a relationship which is textual, physical, and comical:

I saw Moshe and the boychick was soon imprinted like words of indelible ink on the farkakteh page of my brain. Who decides such a thing? Like waking up the morning after shoreleave with an anchor tattooed across your hiney, it isn’t, emes, exactly the result of choice. But I need to be needed and the poor shnook needed me. (18)

While in the Torah, Moishe and Aharon are real brothers and their being together is meant to be, here it is a friendship that is meant to be and it is based on a profound need of the other. The last few pages of the book depict the moment when they both reach the Fountain of Youth, but Moishe takes the more dangerous route and ends up dying. Aharon, however, takes a different route and accidentally (like a schlemiel) stumbles into the fountain. He lives while Moishe dies. But he doesn’t see Moishe’s death. He is separated from him in his last moments:

I pushed myself through. How? Like anyone else, first one foot than the other. Immediately I began to fall. I only knew which way was up because it was the direction I wasn’t going. Then I found my wings and began to flap.

I saw bupkes. Nothing. Nada. I flew in little circles, not knowing where the walls were, not knowing how far was down. I heard the gurgling water. The Fountain or the shpritizing of a kvetchy sea serpent. I could not tell.

Then a rumbling. Some kind of upset tuml in the kishkas of the cave. Then raining down of water from above. Then – Sh’ma Yisroel – the vessels of the world burst open. (332)

The Kabablistic imagery and the revelation are coupled with comedy. He falls into the fountain and feels renewed but then he remembers Moishe. And Barwin goes on to parrot many different motifs from the Torah regarding Moses failure to reach the Promised Land:

Moishe? Where was Moishe? What had happened?

…Though I burned with pain, I searched.

My captain. My Moishe. My other.

He was gone.

Nothing but the unbridled river flowing over the open pit of the Fountain. It was a jumble of broken rock. Moses lost before he reached the Promised Land.

They all were gone.

….

Moishe. My captain. My shoulder. (332-333)

But tragedy doesn’t have the last word. Comedy does. And even though it is bittersweet, it shows us how Barwin writes a “literature on a literature” in which a character develops, in the Bloomian, Biblical sense, and in which time is articulated through relationship. In the end, he survives, like many a schlemiel and like many a Yiddish story, through humor. He embodies the story:

Nu. So there’s the question. And then what happened? Let me tell you. Five hundred years. It happens.I t’s takeh why I have these words.

Was I shpritzed by the Fountain when I fell? Or did it pish on the gantseh megillah, the whole story?

They say when I tell it, it seems as if it goes on forever. Na. I was that story, have become the whole shpiel. Have passed it down to a long line of pisher parrots who also tell it. And tell it to you now. What, they were busy with something else? Any life is just another life out of order.

As long as you have the words. (335)

Aharon, drawing postmodernly on Woody Allen, adds the punchline that he parrots/pirates (albeit substituting the words “I don’t mind dying” with “I want to live forever”):

Emes, I always said: I want to live forever. I just don’t want to be there when it happens. (335)

But the final joke (which is also said earlier in the novel) and punchline of the novel addresses the anxious quintessence (the name of the last chapter) of the Jew/Yid:

Which reminds me: A man goes to the theater with his son.

“One adult and one child,” he says at the box office.

“That’s no child,” the ticket seller says, “He looks at least thirty.”

“I can’t help it that he worries.”

In this joke, Barwin manages to bridge the gap between the two halves of literature while, at the same time, articulating an understanding of Jewishness over time. It is at once comic and tragic. In this joke, we hear family, trauma, and history and we see…a shoulder shrug. Like the parroting narrator, the subject of the joke, the Jew, is at once old and new. While Jews have been stressed by history, humor has helped them (and this novel and its parrot narrator) to journey (and oftentimes flee) and yet live on. And hopefully it will continue to do so. This lesson – which is embodied in Aharon and this joke – is worth parroting. Perhaps this is what comic faith is. As with all jokes, its all in the timing.