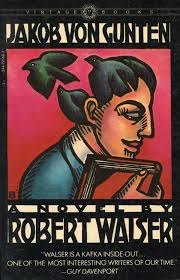

In school we just don’t learn things. We also grow and develop. School is preparation for the real world. And most children take teachers as their role models. Students respect the boundaries that are put between them as they would respect the boundaries between parents and children. These ideas, regarding the meaning and purpose of education, are the backdrop for Robert Walser’s novel, Jakob von Gunten (which was published in 1909). The only difference is that school, The Benjamenta Institute, is not a typical school. Its goal is to teach its students to become servants. The ability of the students to become servants covers a spectrum. Some are more inclined to service and some less. The main character, Jakob von Gunten, is less inclined to be a servant because he has an artistic kind of sensibility. But the fact of the matter is that he is there because he wants to be a servant. He wants to get a job (and he also wants to be humble).

The only thing that gets in the way, it seems, is his…wandering mind and his endless self-deprecation (which he associates with “thought”). His smallness seems to be more aesthetic and less active. He fears that, because he is such a daydreamer, he will never get a job. After all, as Freud duly noted, the artist is a day dreamer. How could he keep a job? What good will training a self-deprecating daydreamer to become a servant be?

One learns very little here, there is a shortage of teachers, and none of us boys of the Benjamenta Institute will come to anything, that is to say, we shall all be something very small and subordinate later in life. The instruction that we enjoy consists mainly in impressing patience and obedience upon ourselves, two qualities that promise little success, or none at all. Inward success, yes. But what does one get from such as these? Do inward acquisitions give one food to eat? (23)

At the outset of the novel, we get a sense that the school looks to make the students feel small. Independence and uniqueness are discouraged:

We are small, small all the way down to the scale of utter worthlessness. If anyone owns a single mark in picket money, he is regarded as a privileged prince. If anyone smokes cigarettes, as I do, he arouses concerns about the wastefulness in which he is indulging. We wear uniforms. Now, the wearing of uniforms simultaneously humiliates and exalts us. We look like unfree people, and that is possibly a disgrace. (24)

The teachers in the school are a brother and sister: Fraulein Benjamenta and Herr Benjamenta. He sees the Fraulein in an endearing manner and laughs to himself about what he learns from her:

It is little, and we are always revising, but perhaps there is some mystery hidden behind all these nothings and laughable things. Laughable? We boys of the Benjamenta Institute never feel like laughing. Our faces and our manners are very serious. (25)

Laughter is seen as a sign of superiority (as Thomas Hobbes would say, it is a sign of mastery over nature). And Jakob is often chastised by the most servile of the students, Kraus, for always being “goofy” and on the verge of laughter (he is called “Jewish” at one point by Kraus, for appearing too “goofy”). He is confused about this very issue because, since he has an artistic sensibility, he knows that laughter is an important part of life. Should he leave it behind? Isn’t it better to by humble and become the perfect servant? Regardless of what he thinks, the school, apparently, doesn’t teach a servant to laugh. It’s inappropriate.

Generally, we pupils do not like to laugh, that is to say, we are hardly able to any more. We lack the requisite jolliness and airiness. Am I wrong? God knows, sometimes my whole stay here seems like an incomprehensible dream. (25)

It seems that Institute is designed to teach students to endure suffering and to give up hope. To be a servant, one must leave these things behind. And this, in Jakob, the want-to-be-servant’s eyes (not the artist’s eyes), is the basis for becoming a man and stop being a “big child.”

Here in the Benjamenta Institute one learns to suffer and endure losses, and that is in my view a craft, an exercise without which any person will always remain a big child, a sort of crybaby, however important he may be. We pupils have no hopes, it is even forbidden to us to nourish hopes for life in our hearts, and yet we are completely calm and happy. How can that be? (94)

When, near the end of the novel, the school starts breaking apart (because the Principal and his sister have some major breakthroughs), things change radically. The teachers do things that, ordinarily, would be considered inappropriate. Herr Benjamenta tells Jakob what he really feels and steps down from his esteemed position in doing so. He becomes vulnerable:

“You’re wondering, aren’t you, Jakob, why I spend my life here in the Institute so lethargically, so absent-mindedly, as it were? Isn’t that so? Have you noticed it? But the last thing I want is to lead you astray into giving outrageous answers. I must confess something to you, Jakob. Listen, I think you’re an intelligent and decent young person. Now, please, be cheeky. And I feel that I must confess something else to you: I, your Principal, think well of you. And a third confession: I have begun to feel a strange, a quite peculiar and now no longer repressible preference for you.” (96)

Jakob is startled and his whole perspective on the school and his task changes:

And now I noticed that the Principal, this gigantic man, was trembling slightly. From this moment, some common bond was between us. I felt it, yes, I didn’t only feel it, I knew it. (96)

He realizes that he is, at this moment, no longer a pupil (96). He “had just risen to the most unpupil-like heights”(96). This really confuses him. He wonders if he and Herr Benjamenta are friends. But he pushes away these thoughts. Its better to just act and not think; to accept and not to question what has just happened.

Strangely enough, immediately after going over this experience, he realizes that he still hasn’t been able to “find a job”(96). The two are, in his mind, connected. And Herr Benjamenta confirms this toward the end of the novel when he notes how, after the Institute is closed, everyone except for Jakob will have a job. The reason: the Principal asks Jakob to accompany him in his Quixotic journeys.

But the Principal is not the only one to confide in Jakob. His sister does as well:

Something incomprehensible has happened. Perhaps it’s of no significance at all. I’m not much inclined to let myself be overcome by mysteries. I was sitting all alone in the schoolroom, it was almost nightfall. Suddenly Fraulein Benjamenta was standing behind me. I hadn’t heard her come in….She asked me what I was doing, but in a tone of voice that made an answer unnecessary. She said, as it were, even in asking, that she already knew. Wat then happens, one naturally doesn’t answer. She p laced her hand on my shoulder, as if she were tired and needed support. Then I felt strongly that I belonged to her, that’s to say, or is it, that I did belong to her. Yes, simply belonged to her. (99)

They do things silently. They walk together. She guides him. What follows is a kind of dream. However, there is a scene which follows that is much more grounded in what appears to be reality:

“Jakob, quite seriously now, listen. I must whisper something to you. Do you want to hear it or would you rather slip into your room here?” “Tell me what it is, Fraulein, I’m listening,” I said, full of anxious expectation. Suddenly the instructress gave a great shudder. But quickly she controlled herself and said: “I must go, Jakob, I must go. And it will go with me. I just can’t tell you. Perhaps another time. Yes? Yes, perhaps tomorrow, or in a week?” (116)

And then she breaks all boundaries and asks him:

“Tell me, Jakob, do you love me a little? Do I mean anything to you, to your young heart?” She stood there in front of me, her lips pressed angrily together. I quickly stooped to her hand, which unspeakably sadly down against her dress, and kissed it. I was so happy to be allowed to tell her now what I always felt for her. (118)

After she leaves him, he notes how “everything changed in this once so tyrannical Benjamenta Institute!”(118). Now “everything is collapsing, the classes, the effort, the rules”(118). But he is confused. Is this good or bad? He feels good (because of the moment of love and breaking boundaries) but he also feels bad.

Following these profound moments, two violent and sad things happen. First of all, the Principal becomes violent with Jakob when he fears that Jakob (who is more than 20 years younger than the 40 year old principal) will leave him alone and not journey with him into the wilderness. This shocks and confuses Jakob. But the second thing thing that happens is much more crushing: the Fraulein commits suicide (143).

How can he, after all this confusion and tragedy, go from being an artist to being a servant? What happens when he no longer seems to have a friend and no longer has a….lover?

At this moment, Walser has Jakob encounter Kraus (who is not an artist, but a servant who…doesn’t laugh or even think of his personal feelings). Kraus faces the death with the required respect and takes leave of the school and Jakob for work in the world as a servant. His advice to Jakob is powerful. He suggests that it may be impossible for an artist to be a servant; since the artist can’t stop thinking or feeling rather than doing. Jakob may always be a man-child (schlemiel) in Kraus’s eyes:

I hope that worry and toil will take you into their hard, vice-breaking school. Look, Kraus is saying hard words. But perhaps I mean it better for you, Brother Funny, than people who would wish you good luck in your gaping face. Work more, wish less, and something else: please forget all about me. I would only be annoyed if I felt that you might have one of your shabby cast-away, dancing, here-today-and-gone-tomorrow thoughts left over me. (146)

Now Jakob must decide. Now that Kraus and Fraulein Benjamenta are gone, will he go with the Principal on a “journey into the wilderness”?

Jakob has a dream of a woman of beauty laying in a colorful meadow. He feels “happy” for a “fleeting moment” when he “thought of This person”(152). She floats away like a water vision and then “he” comes into focus. Jakob realizes that it is the Principal. He sees him, not it a meadow, but in a desert on a horse (looking like a cross between an “Arab” and a knight). They travel through the desert, the horses become camels, time passes, as in a dream, imperceptibly (153). People and space also passes in a graceful manner as they leave “culture” behind:

The customs of the people we saw delighted us. There was something mysterious, gentle, and delicate in the movements of these countries. Yes, it was as if they were marching along, no, flying along. The sea extended majestically like a great blue wet world of thought. One moment I heard the wingbeats of birds, then animals bellowing, then trees overhead. (153)

As the reader can see, Walser describes this journey as touching all the senses. It resembles something one might find in a Cervantes novel. They are the heroes of a journey; the Principal, so to speak, is Don Quixote and Jakob becomes Sancho Panza. When Jakob thinks, in his dream, that this arrangement and journey is “well and good”(153), he wakes up to see that he is sleeping next to the Principal. He wakes him up and tells him that, yes, he will go on the journey with him into the “wilderness.” As readers who (perhaps) have jobs and work, many of us would read this as a strange (and even pedophilic) kind of fantasy. How could Jakob do this? Isn’t he totally renouncing the world now?

In the last paragraph, Jakob tells the reader that one must not think if one is to embark on a journey into the unknown. He assures the reader and himself that this is right and necessary. To do this, he must reject being just a zero. And, for him, being a zero has a lot to do with what he calls thinking (which is, in effect, always reductive). By thinking, he is reminded how small he is. He wants to live and go out into the wild (not, it seems, the world). And thinking seems to get in the way.

The pupils, my friends, are scattered in all kinds of jobs. And if I am smashed to pieces and go to ruin, what is being smashed and ruined? A zero. The individual me may only be a zero. But now I’ll throw away my pen! Away with the life of thought! I’m going with Herr Benjamenta into the desert. I just want to see if one can live and breathe and be in the wilderness, too, willing good things and doing them, and sleeping and dreaming at night. (154)

But in the very last words of the novel, he realizes how hard it is not to think. It is the struggle he must engage in if he is to depart in a joyful manner. Walser formulates it as a kind of leap of faith:

What’s all this. I don’t want to think of anything more now. Not even God? No! God will be with me. What should I need to think of Him? God goes with thoughtless people. So now adieu, Benjamenta Institute. (154)

In other words, Jakob’s education doesn’t lead him to be a servant like Kraus. He is a servant of another kind, whose service of God is found in a kind of motion that is…thoughtless. And instead of going out into the world and getting a job, he clings to nature like the schlemiel that, as Hannah Arendt suggests, made its debut in Germany through the German Jewish poet Heinrich Heine. For Heine and, it seems, for Walser, the only way out of one’s misfortune is to go on a kind of Quixotic journey into the wild and playing a Sancho Panza to a Don Quixote.

It is well known that Franz Kafka read Walser and, as Walter Benjamin well knew, Kafka was fascinated with the relationship of Sancho Panza and Don Quixote. Benjamin argued that “The Truth of Sancho Panza” was Kafka’s greatest parable. Based on his reading, Benjamin ended his Kafka essay with a reflection on the parable. The main point he wished to make is that both he and Kafka were Sancho Panzas following a Don Quixotes (and that this would, as Kafka wrote, provide them with endless “entertainment and philosophical amusement” for the “duration of his days”). While it is not quite clear who Kafka or Benjamin took as their Don Quixote, Walser suggests that it would have to be someone who broke out of an institution and turned the student into a friend; a friend who would….journey with him from the ruins of the school into the wilderness.

The question I have, however, is what this suggests. Doesn’t this mean that one doesn’t enter the world? And wouldn’t that suggest that, though the two are small in the worlds eyes, their not working and moving is actually something quite big? The world doesn’t exist for Jakob and the ex-Principal. They are worldless. Their journey seems, like his dream, to be an endless movement through time and space. And, as Walser suggests, that movement must leave thought behind and may actually be a movement that is…with God.

But one need not accept this and can laugh at these fools from the perspective of the world. That’s the reader’s choice. It’s a decision about how to leave school and where to go. And this prompts the most important questions, which I’ll end with: What will we do when we leave? And what is the best way to leave an institution that is falling apart? And what is Walser suggesting about living on? What does it suggest about the meaning of smallness, service, and faith?

And instead of going out into the world and getting a job, he clings to nature like the schlemiel that, as Hannah Arendt suggests, made its debut in Germany through the German Jewish poet Heinrich Heine. ” Interesting! Arendt talks about schlemiels? I didn’t know she was that hamish! IMO it is an illusion to think one can not enter the world. One is already in it. And anybody extolling the virtues of thoughtlessness has those virtues beyond reach, because he or she has thought to think that. But that’s okay by me: I think if you don’t think for yourself you will end up being victimized by them that do.

Yes,she did. Her essay “The Jew as Pariah” is a very important text in my schlemiel project. Love the quip. And yes, that’s a good point. Walser’s Jakob thinks of himself as a zero but he’d rather just keep on moving and forget about it but…the motion implies that no job should keep him stuck in one spot. Q: tell me how victimization figures in your reading of the schlemiel (your other comment suggests victimization as well; but from the other end).

If you tell people you are a shlemiehl you avoid taking responsibility for bad things that happen to them as the direct result of your actions. It is the perfect alibi for a victimizer.