Irving Howe initiated his letters to Ruth Wisse about Sholem Aleichem by staking his main claim that, based on his own experience of Sholem Aleichem’s stories, he must go against the grain and state that they, like all stories of the Schlemiel (from Chelm to Hershel Ostropolier), have “their undercurrents of darkness.” Throughout Howe’s letter, we find a repeated emphasis on how odd he now feels when he reads Aleichem: “And now, in reading Sholem Aleichem, I find myself growing nervous, anxious, even as I keep on laughing.” This troubled laughter reverberates throughout the letter.

Although she agrees in many ways, Ruth Wisse is suspicious of Howe’s way of speaking. And despite the fact that she can understand its source and agrees with it – to some extent – she puts forth a different tone and a different emphasis. As the epistolary correspondence moves on, this becomes more and more apparent.

Wisse initiates her epistolary response to Howe by noting that what he is saying was also said by the Yiddish critic and early admirer or Sholem Aleichem, Ba’al Makshoves. According to him, Wisse tells us, Aleichem “conjures up the collective anxiety and then dispels it magically, laughing the danger away.” Reflecting on this, Wisse argues that Aleichem’s contemporaries may have “taken the uncertainties for granted” and “enjoyed the relief he alone provided.” But she agrees with Howe and reflects that “nowadays his name has become such a byword for folksy good humor, innocent ‘laughter through tears,’ that we are surprised to rediscover the undertone of threat in his work.”

She concedes that it might be their shared “modernist bias” that makes them frown upon contemporary kitsch representations of Aleichem’s work; nonetheless, she does note that Aleichem was aware of the “fatal weakness of the culture.” It comes through in the “narrator’s sense of his own shared culpability in having brought it (the culture) low.”

In other words, he is a “self-conscious” modern artist and, like Howe and Wisse, he has a modernist bias. And unlike “Tevye, Sholem Aleichem encouraged his children’s Russification.” But, and here is the difference, Aleichem knew he was “confined to a Jewish fate” and was the “product of ‘tradition.’” He also left for American and made and remade himself like many other Jews fleeing a slowly dying Jewish life in Eastern Europe.

Although she acknowledges the modernist bias and the “ferocity” we see in Aleichem, Wisse wants to take some of the sting out of Howe’s reading. And she does this by lending more emphasis on Aleichem as the artist who, she believes, can do the Jewish people some good. Making reference to an Aleichem story entitled “Station Baranovitch,” Wisse notes how the narrator and the author share a similar task; the task of the story teller:

The fate of Kivke (the place in the story) and the Jewish community are ultimately in the hands of the gifted story teller whose untimely departure at Baranovitch constitutes the story’s only fatal event. The artist can transform reality at will – a potent charm in desperate times – but his magic is subject to temporal claims.

Like her brother, David Roskies (who in his book A Bridge of Longing: The Lost Art of Yiddish Storytelling, looks into the power of the Magid, “storyteller,” to bridge the past and the present), Wisse wants us to pay closer attention to the storyteller. Nonetheless history does matter for Wisse as much as it does for Howe. But history is balanced against the powers of the story teller: as we see in Wisse’s words above, the storyteller’s “magic is subject to temporal claims.”

In response to Wisse’s counter-balancing of the story-teller and his magic to the horrors of history, which he addresses, Howe takes note once again of the kitschy view he is trying to think through with his emphasis on the undercurrent of horror in Aleichem. He justifies his challenge in view of this:

To see Sholem Aleichem in this way seems a necessary corrective to the view, now prevalent in Jewish life, that softens him into a toothless entertainer, a jolly gleeman of the shtetl, a fiddler cozy on his roof.

The words “toothless entertainer,” “jolly gleeman of the shtetl,” etc are meant to cajole and insult those who fall for kitsch and masscult. He goes on to say that Aleichem is a “self-conscious” artist and not a “folk writer.” The problem with this claim, however, is that Wisse (like her brother Roskies) believes that Aleichem, although a self-conscious writer, was still drawing deeply on the folk tradition of the Magid (story-teller). In response, Howe notes that he came out of this culture -where the storyteller and the audience were intimate – but that he was not bound by it. Nonetheless, Howe himself is perplexed as his thesis – influenced by Saul Bellow – about comedy and horror being interchangeable is being challenged by Wisse who is looking for more balance between the powers of the story teller and the challenge of history.

The word Howe uses to distinguish his reading of Aleichem from the older type of Magid – and to “balance” the Jewish tradition with the modern artist – is “quizzical” (a word which, as we shall see, Wisse plays on):

Sholem Aleichem stands as both firm guardian of the Jewish past and a quizzical skeptical Jew prepared (as the story of the Tevye stories makes clear) to encounter and maybe accept the novelty and surprise of modern Jewish life. It’s just this balance, so delicate and precarious, that I find so enchanting in his work.

In “the end,” says Howe, what we also hear in Aleichem’s folkloristic tales is a “quizzical voice.” Howe goes on to say of this voice that it “tells of madness…but so long as we can hear that voice, we know the world is not yet entirely mad.” Indeed, Howe sees quizzical voice as offering a kind of salvation for modern readers such as himself who see the world as mad.

But this mad, quizzical voice is not funny. And its salvational aspect is, because it is mad, still troubling. Nonetheless, Howe agrees that the traditional and the modern should be balanced by way of balancing the folk voice (the voice of the Jewish tradition) with the “quizzical” voice.

In response, Wisse next letter pushes Howe to think more about the meaning of balance so as to take the edge off of his modernist obsession with the “quizzical” and the uncanny. She notes that of the three greatest Yiddish writers – Mendele, I.L. Peretz, and Sholem Aleichem – all tried to find a “balance” between tradition and modernist writing but each of them tilted too much in the direction of towards the skeptical: “The strain of this divided existence, and the resentment, shows in their work.” However, Aleichem is “different”; he achieves balance:

Sholem Aleichem is different. Though he too felt the impending break in the ‘golden chain’ of Jewish tradition, and felt the cracks within his own life, he makes it his artistic business to close the gap.

Wisse goes so far as to say that “wherever there is a danger of dissolution,” the stories “work their magic in simulating or creating a terra firma.” In other words, we need to pay attention to the crisis but, more importantly, we need to see how Aleichem addresses it and “balances” out tradition. As Roskies, Wisse’s brother might say, Aleichem provides a “bridge” and that, for Wisse, is more important that the “quizzical” voice that Howe hears in Aleichem’s work.

To be sure, by Terra Firma Wisse even goes so far as to agree with the Yiddish critic Borukh Rivkin that Aleichem gave the Jews of Eastern Europe a “fictional territory to compensate for their lack of a national soil.” Wisse’s reading, here, is echoed by Sidrah DeKoven Ezrahi in Booking Passage: Exile and Homecoming in the Modern Jewish Imagination. In her book Ezrahi sees this move, for her embodied in the post-Holocaust American translation project of Howe, Bellow, and Feidler, as the creation of a “virtual shtetl” – and, after the founding of Israel, this substitute land (think of George Steiner’s “text as homeland”) comes into question.

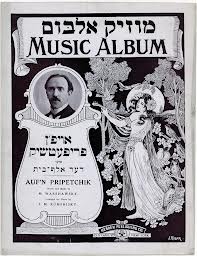

In addition to finding the necessary “balance” in terms of rescuing tradition from dissolution, Wisse claims, in response to Howe, that even though Tevye is not the Vilna Gaon, he is “the original stand-up comic, playing to an appreciative audience of one: his impresario, Sholem Aleichem, who then passes on this discovered talent to his readers.”

In other words, Wisse looks to underscore the ameliorative aspects of Jewish humor which are a response to history. She does this by pointing out that Aleichem not only balances out tradition but he does so in the spirit of the “original stand up comic,” which he created.

And this speaks to Wisse’s recent book No Joke: Making Jewish Humor, since Wisse looks for a humor that balances tradition instead of destroying it by way of extreme/excessive sarcasm.

As I have tried to show in this blog entry, Wisse also thinks that extreme skepticism (the “quizzical” tone that Howe speaks of with Aleichem) can also pose a threat. That’s why she introduces the notion of “balance” into the epistolary exchange with Howe.

(In the next blog entries that address this epistolary exchange, I’d like to bring out this subtle contrast between Howe and Wisse so as to show how the schlemiel can be read in terms of the tension between tradition and modernity. If an author looks at the schlemiel in too skeptical or quizzical a light, the Jewish tradition may be compromised. Nonetheless, Wisse does agree that skepticism must be there. As I noted above, for Wisse it seems to be a matter of emphasis. She would agree that there is a strange, dark “undercurrent” with the schlemiel, but how much of an undercurrent? How does it relate to – or balance out with – the comic element? Is that what makes for Jewishness? Or does radical skepticism and irrevernace, as we see in writers like Sholom Auslander or even Phillip Roth, mark Jewishness as “quizzical?”)