There is a long history of films, books, and plays that depict the assimilation of Jews into America. Many of these works include scenes that articulate the loss of faith which can lead to either a good or a bad ending. On the one hand, think of The Jazz Singer (1927), a film that puts the heat on: the son of a cantor must make a choice between keeping his father’s traditions and going into show business.

It has a good ending.

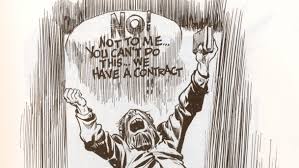

On the other hand, think of Will Eisner’s A Contract With God, a graphic novel which depicts a religious Hasidic Jew, Frimme Hersh’s loss of faith and dispute with God. He, like Job, takes up an argument with God over not living up to his side of the “contract” (covenant) when his daughter is tragically taken away from him. His suffering breaks him since he sees that a life of faith doesn’t give the rewards that it promises. In anger and resentment, Frimme rejects his faith. He is a broken man.

But his brokenness turns into a drive to sin. Eisner depicts this as a movement from an emasculated masculinity (which he associates with the humility of faith) to male aggressivity. America seems to bring out something from the Jew that simply didn’t exist in Europe. He goes from being Job to being his opposite. But then, at a certain point, he experiences an emptiness.

In the end, he wants a new contract with God to fill the emptiness of his new, American life. He’s willing to give faith a second chance. However, before the new contract is drawn up, he dies. He doesn’t get to live a new kind of Jewish life in America. He dies, naked, secular, and alienated.

In my last post on Joseph Roth’s Job: The Story of a Simple Man, I briefly touched on Mendel’s loss of faith and the final miracle at the end of the book (with not only the return of his son Menuchim, but also the miracle of the photograph, which opens his eyes to his newly discovered daughter-in-law and grandchildren).

Here, I’d like to take a much closer look into what fomented Mendel’s breakdown of faith as well as his return to life by way of a miracle. What he experiences presents a different kind of possibility for the Jewish immigrant than we see in either the Jazz Singer or Eisner’s Contract With God. Roth suggests, on the one hand, the family and group of friends (and not just technology – I will return to this) as a saving grace, and on the other, the possibility of miracles in America. His promise is, as Levinas might say, in the future, in fecundity. Without that, his faith would remain broken.

Before introducing the major turn of events in Mendel’s life, Roth depicts the American scene for Mendel, his wife, and children as one of health and excitement. Mendel wants to stay up all night and partake in its life-giving energy: “They spoke of the theater, of society, of politics. He listened and dozed. When Deborah called, he opened his eyes. ‘I wasn’t asleep,’ he would assure them. Mac laughed, Sam smiled, Miriam and Deborah whispered together. Mendel would stay awake a while, and then nod again”(150).

When he dreams, we see an American dream take shape which is, more or less, like a circus. But it is briefly interrupted by the memory of Mendel’s crippled son,Menuchim, who he left behind in Europe:

He dreamt of events at home, and things which he had only heard about in America: theaters, acrobats and dancers in red and gold, the President of the United States, the White House, the millionaire Vanderbilt, and ever and ever again – Menuchim. The little cripple was mixed up with his dreams of prima donnas in red and gold. (150)

Following the dream, the narrator sums up America in one long sentence:

Americans were healthy, their women pretty, sport was important, time was money, poverty was a crime, riches a service, virtue was half of success, and belief in oneself the whole of it, dancing was hygenic, roller-skating a duty, charity was an investment, strikers were enemies of mankind, agitators instruments of the Devil, modern machinery a gift of God, Edison world’s great genius. (151)

America is the anti-thesis of the Europe he came from with his family. Thinking of the future grandchild of his son Sam (Sam is the child who left Europe and brought his family to America), he experiences a new kind of hope: “The world will be very beautiful, thought Mendel. How lucky my grandchild is! He will live through it all!” (151). However, this hope is overshadowed. He thinks he will die before he has a grandchild.

But, at that moment, another hope comes to him: “But he had one hope left: to see Menuchim. Sam or Mac would go over to fetch him. Perhaps Deborah would go to”(151). In other words, he can’t live his American future – no matter how bright – without coming to terms with the past. He defied the Rabbi by leaving Menuchim behind. That is the secret thought in the back of his head and it may, at this moment in the novel, be his last remnant of faith.

When Mendel thinks about his wife while she is sleeping, he wonders why they are together. He sees his desire for her as faded into the past and seems to see their relationship in practical terms. He then turns to the Bible for vindication: “It is written, it is not good for man to be alone. Thus we live together”(153). He doesn’t quite understand why it is more than something practical. It all comes to him when he loses his dearest family members one by one.

It all starts with Sam going off to fight in World War I. Sam, convinced that “America isn’t Russia,” takes up the cause of the War and believes that he would be one of the “high officers” who would survive. Mendel disagreed since he had already lost “one son” (Jonas) to the war (although no one, to the very end of the novel knows if he is dead or alive). Mendel couldn’t stop him. As Sam leaves, Mendel reflects: “Perhaps America was a real fatherland, war a duty, cowardice shameful, and death – when one was attached to the regimental staff – out of the question”(161). But then he thinks that he “should have said” stay because he finally had some good fortune: why experience more misfortune…if Sam were to die.

His worst fears come true.

Roth depicts the news as being transmitted in the context of a family moment at the table in the winter. After sitting together for a while at a table – following some time while Sam was away – Mendel, being so familiar with misfortune (a Russian Jew, as Roth puts it) “knew…what was coming.” His daughter, Miriam, was hiding a secret:

Silence reigned for a few seconds. Miriam did not speak. It was as though she hoped that her mother or father would free her, by a question, from announcing her news. She stood still, and was silent. None of the three moved. (164)

When Miriam speaks, the damn breaks loose and Deborah, her mother and Mendel’s wife, breaks down. Her body changes. She starts pulling her hair out. Miriam “sank to her knees.” Deborah’s hands “were like a pale, fleshy, five-footed animals, feeding themselves on hair”(165). Deborah goes insane and starts singing. She dies out of shock: “All of a sudden a suppressed scream came from Deborah’s breast. It sounded like the rest of the melody which she had been singing, a broken bursted note. Then she fell from her chair”(166).

Mendel speaks to his dead wife as if she was alive and his words reflect his loss of faith and total alienation. He loses his identity and much else…because of America:

“You are well off, Deborah,” he said to her. “It is only sad that you have no son left to mourn you (as he thinks both Jonas and Menuchim are dead). I myself must say the prayer for the dead, but I will soon die, and no one will weep for us. Like two tiny specks of dust, we shall be scattered…I have begotten children, your womb has born them, death has taken them. Meaningless and full of poverty was your life….You are dead and buried. Towards me He shows no pity. For I am dead, and yet live. If you can, pray for me, that I shall be stricken from the book of the living….I eat and drink, pray and breath. But my blood congeals, my hands are limp, my heart is empty. I am no longer Mendel Singer, I am but the remains of Mendel Singer. America has killed us. America is a real fatherland, indeed, but a death dealing fatherland. What was life, with us, is death here….You are buried in America, Deborah, and I, too, will be buried in America”(170-171)

Following this, we learn that Miriam has lost her mind (172). And like Job, Mendel’s life worsens and his faith becomes thinner and thinner:

They left him. Mendel went to the window and watched them (his son’s friend Mac, and Sam’s wife, Vega) get into the car. It seemed to him that he must bless them, as though they were children who start out on a journey which may be hard or may be very happy. I shall never see them again, he though; then – I shall not give them my blessing, either. My blessing might be a curse, coming from me it could only harm them. (177)

Now he lets go of the weight that comes with faith:

He felt light, lighter than ever in all his years….He was alone – alone. Wife and children had surrounded him and had hindered him from bearing his pain…..Now, at last, he indulged his misery in triumph! There was only one relationship still to be broken. He had prepared to do it. (178)

But then he does the deed.

He gathers up all of his religious objects and burns them (178). As Eisner might say, he tears up his contract with God and becomes one with the Biblical Job character:

“It is over, all over; it is the end of Mendel Singer!” he cried, and his feet stamped in time to the tune, so that the floor-boards rumbled and the pots on the wall began to rattle. “He has no son, he has no daughter, he has no wife, he has no country, he has no money! God said: I have punished Mendel Singer! For what has he punished him?” (179).

When his neighbors come up to see what’s going, we have a scene that we could find in Job; namely, different opinions about God and faith by his friends.

Mendel concludes, at the outset, that religion is more or less masochistic and God is sadistic: “God is cruel, and the more one obeys Him the more brutally He treats one…The weakness of man tempts His strength, and obedience awakens His scorn”(181).

And, ironically, when he is told that his case is similar to Job, he disagrees because he hasn’t seen any miracles (in the end) and doubts they will come. No one, he says, will be resurrected and he doubts he will see either Jonas or Menuchim. He insists (without knowing for certain) that they are dead (183).

Reflecting on Menuchim, he thinks that Menuchim was sick because “it showed that God was wroth with me. It was the first blow, which I didn’t deserve”(183). Even so, one of the neighbors, Menkes, argues that it is possible that a miracle can happen: maybe Menuchim is alive, Jonah is in prison, and Miriam can be cured from her madness.

He is not convinced that no miracles are possible anymore. In his rejection of God, he says that the “Devil is kinder than God”(185). He seems to have washed his hands of God, completely. There would be no happy ending because, to his mind, God is a sadist. Tragedy, not comedy, is the lot of the man of faith.

As a part of his refusal, Roth shows Mendel in the midst of the month of Elul (before high holy days). The community comes to his building and even makes a synagogue in his room. He lets them but he doesn’t participate in the prayers. They pray at his home on Yom Kippur. But “Mendel Singer stood, black and silent, in his everyday clothes, in the background, near the door, unmoving. His lips were closed, and his heart was a stone. The song of Kol-Nidre rose like a hot wind. Mendel Singer’s lips remained closed, and his heart a stone”(192).

Silence reigns. But after the war ends, “the festive sound of a happy world” returns (196). Roth takes up the phonograph as a technology that (partially) breaks the stone heart of Mendel. He brings it to his home and listens every day. He listens to all kinds of music (196). He is astonished by the miracle of technology and this gives him some hope (197). When he discovers a song called “Menuchim’s song,” he becomes dour yet, at the same time, he starts thinking of Menuchim and how the boy, who only spoke one word, “mama,” may get to sing and he may hear it someday. The important thing is that the miraculous is conveyed through technology and it makes him entertain the possibility of something he has long denied as a result of his suffering and affliction – something he let go of when he deemed God a sadist and faith masochism.

The miracle happens on the night of Passover. The influence of music is apparent when, throughout the ceremony, Mendel “sways” to the “music of others”:

And even Mendel became milder towards Heaven, which four thousand years ago had generously lavished such marvelous miracles, and it was though, because of God’s love for his whole people, Mendel cold almost be reconciled with his own fate. He still did not participate in the song, but his body swung backwards and forwards, cradled in the song of the others. (214)

When a stranger from Russia joins them, who the narrator calls a Kossak, Mendel has the courage to start asking questions about his home, about Jonas and Menuchim. Like Joseph in the Bible, the stranger conceals his identity, he is really Menuchim. But Mendel doesn’t know until, at the very end, he reveals his identity.

Menuchim tells of how he was cured of his illness by a medical institute in Russia and was taken in by a doctor who took a liking to him. We also learn that he is – like the last name of his father and his own name – a “singer.” When he reveals that he is the singer of “Menuchim’s song,” which, as we saw earlier, enlivens Mendel to recall his missing son, everything shifts. Mendel tells him that his wife (Menuchim’s mother) has died, but he still shies away from asking about Menuchim. Roth portrays Mendel’s inner struggle over whether or not he should say the words. But it is Menuchim who says the words “Menuchim is alive!”

Mendel laughs and weeps as one would expect in the pronouncement of a miracle (as one sees at the end of the Joseph episode when Jacob realizes that Joseph is still alive). And now we see another breakdown of Mendel’s body. Menuchim prompts it when he whispers the words of his deceased wife to Mendel so as to remind him that the words of the Rabbis are true: “Pain will make him wise, ugliness good, bitterness mild, and sickness strong!”(227). The neighbors all witness the miracle and Menkes, “the most thoughtful of all of them,” sums up the entire journey of brokenness and faith: “We tried to comfort you, but we knew it was in vain. Now you in the flesh experience a miracle! As we mourned with you, so we rejoice with you now. Great are the wonders of the Eternal, today, as they were a thousand years ago! Praise His name!”(228)

Mendel repents. His life is different now. Menuchim takes care of him. And he tries to come back to life although he is near death. The circle is completed when he sees the photo. It like the phonograph brings him closer to life. In the photo he sees that he has not only a daughter in law but real grandchildren. He has a future. And this is what completes his faith.

What is so fascinating about this process is that a phonograph and a picture help him to live and return to faith. Modern medicine does as well, since it cures Menuchim. Faith, Roth seems to be telling us, is a process of breakdown and recovery; and, in America, in the modern world, it takes on a new form as the miraculous is a part of our everyday life. But, more importantly, it is the community (Mendel’s larger family) that Mendel stays in proximity to, although he doesn’t share their faith. It is the miracle of being-together during morning, Yom Kippur, and Passover that is the condition for the possibility of Mendel’s process of breakdown and recovery. And it is the community that gives him the phonograph. Without them and their kindness, he could no longer hear the sounds of life and the joys of world; without them these sounds of hope would not exist. Technology is a part of this organic whole; it transmits the sensory; it facilitates healing.

Roth’s story works on many levels. But, unlike Eisner’s Contract With God or the Jazz Singer it shows an organic process of the deterioration and renewal of faith. These two stories – one of assimilation – and the other of broken faith lack these elements. And while Eisner’s stops short, Roth does not. He suggests that without community and hope, Jewish life in America (for the immigrant) is a tragedy. The simple man, as his subtitle suggests, may be ruined but he holds on to a small thread. His humility and his desire to not shock others may be his saving grace. And it may, as Roth suggests, be the key to faith for a hyphenated Jew who, like Mendel Singer and Job, may – despite endless misfortune – be in for a surprise or two. That’s a story – a comedy – that found its expression, as well, in Charlie Chaplin. Perhaps, because of its comic turns and twists of fate and stokes of luck, Roth is telling us that were it to be a European story and not an American one the ending would be tragic not comic. After all, he saw pogroms and the rise of Hitler and knew, like Shalom Aliechem, that life for Jews in Europe was coming to an abrupt end.