With the rise of anti-semitism in America – which I have experienced, personally; and see on social media, perpetually – I have been starting to think more about what it is and what we can do to – if possible – counter-act it. One era that I have studied in depth and written on in many essays and book chapters, is the period before, during, and after the Holocaust. German Jewish thinkers like Walter Benjamin, Hannah Arendt, Gershom Scholem, and Theodor Adorno have been on my radar for some time.

Today, I look to what Adorno’s thoughts were after anti-semitism had its run through Germany, destroyed the country, and annihilated millions of Jews. How did it germinate, so to speak, in Germany? One thought that came to me is that what we are seeing right now with paranoia on social media about this or that group and its power is a symptom of anti-semitism. Adorno, in an essay entitled, “The Meaning of Working Through the Past,” sees the forces around nationalism as “intentionally self-deluded.” For him, nationalism is the “heritage of barbarically primitive tribal attitudes” that was against anything different. As the nation decayed, so to speak, it became, according to Adorno, “sadistic and destructive.”

Nationalism does not completely believe in itself anymore, and yet it is a political necessity because it is the most effective means of motivating people to insist on conditions that are, viewed objectively, obsolete. This is why, as something ill at ease with itself, intentionally self-deluded, it has taken on grotesque features nowadays. Admittedly nationalism, the heritage of barbarically primitive tribal attitudes, never lacked such traits altogether, but they were reined in as long as liberalism guaranteed the right of the individual—also concretely as the condition of collective prosperity. Only in an age in which it was already toppling has nationalism become completely sadistic and destructive.

For Adorno, the energy behind nationalism (“nationalism as a paranoid delusion system”) was “paranoia,” which, for the Nazis, was a “persecution mania.” It was “contagious.”

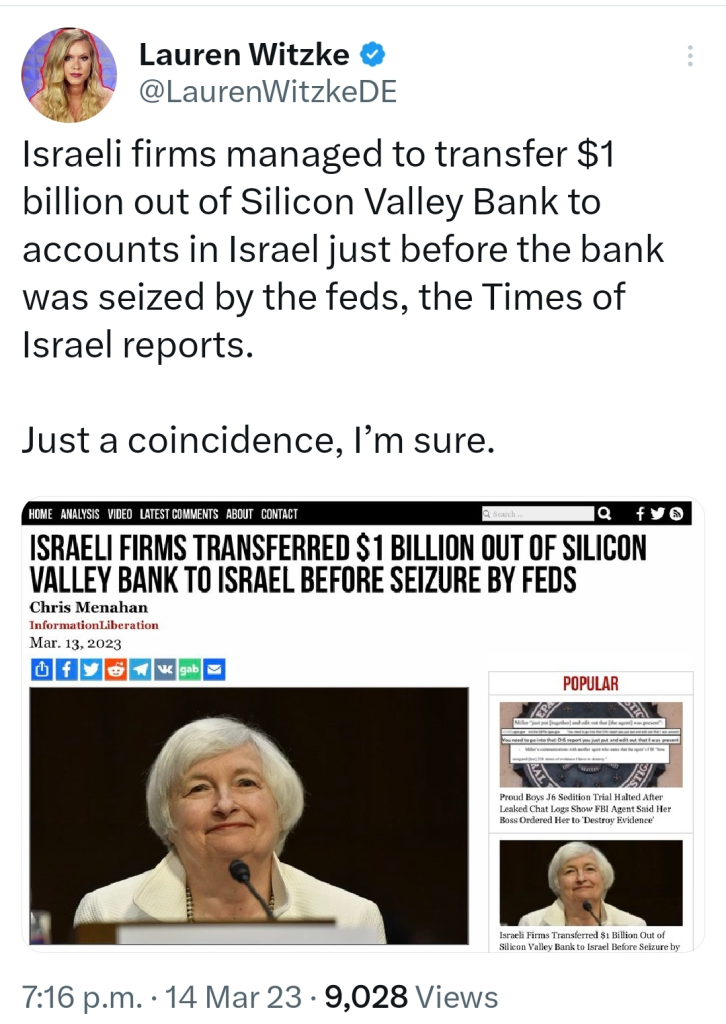

We see something like this today, on social media with anti-semitism in which anti-semites – like Kanye or his white supremecist muse, Nick Fuentes -have the paranoid belief that Jews control everything and are destroying not just the nation but they, themselves, personally.

The rage of Hitler’s world against everything that was different—nationalism as a paranoid delusional system—was already of this caliber. The appeal of precisely these features is hardly any less today. Paranoia, the persecution mania that persecutes those upon whom it projects what it itself desires, is contagious. Collective delusions, like anti-Semitism, confirm the pathology of the individual, who shows that psychologically he is no longer a match for the world and is thrown back upon an illusory inner realm.

This fascinating part is that the anti-semite is “no longer a match for the world” and, in his retreat to his or her keyboard, is “thrown back upon an illusory inner realm.” In other words, the anti-semite, in taking the world as the enemy of the average American, etc cannot live in this world where it used to dwell so it he/she is thrown back into their private illusory worlds that are supported by other people tweeting, instagraming, etc from their lonely keyboards.

Anti-Semitism is so difficult to refute because the psychic economy of innumerable people needed it and, in an attenuated form, presumably still needs it today. Whatever happens by way of propaganda remains ambiguous.

Anti-semitism, in other words, is a “collective” desire. It is a desire based on paranoia that, because it is needed – due to alienation, loneliness, and confusion – is urgent and pressing. After arriving at this thought, Adorno turns to someone who enjoyed the dramatization of The Diary of Anne Frank. What, one may ask, is the connection of this dramatic experience to anti-semitism or persecution mania?

I was told the story of a woman who, upset after seeing a dramatization of The Diary of Anne Frank, said: “Yes, but that girl at least should have been allowed to live.” To be sure even that was good as a first step toward understanding. But the individual case, which should stand for, and raise awareness about, the terrifying totality, by its very individuation became an alibi for the totality the woman forgot. The perplexing thing about such observations remains that even on their account one cannot advise against productions of the Anne Frank play and the like, because their effect nonetheless feeds into the potential for improvement, however repugnant they also are and however much they seem to be a profanation of the dignity of the dead.

This person, for Adorno, only sees the individual, Anne Frank, she doesn’t see the “terrifying totality,” that made Anne Frank into an animal to be hunted and killed by Nazis. But, notes Adorno, the effect of this play can still “feed the potential for improvement.” While a play like the Diary of Anne Frank, seems to be a “profanation of the dignity of the dead” (something Eli Weisel or Paul Celan might say), it still can bring someone to a potentiality for “improvement.”

But Adorno has his doubts because he does not think the “genuine” anti-semite’s experience of real Jews – not fictional or dramatized ones – can efface his or her anti-semitism. Why? Because this presupposes that an anti-semite has the capacity for experience. On the contrary, writes Adorno, “the genuine anti-Semite is defined far more by his incapacity for any experience whatsoever, by his unresponsiveness.”

All too often the presupposition is that anti-Semitism in some essential way involves the Jews and could be countered through concrete experiences with Jews, whereas the genuine anti-Semite is defined far more by his incapacity for any experience whatsoever, by his unresponsiveness. If anti-Semitism primarily has its foundation in objective society, and only derivatively in anti-Semites, then—as the National Socialist joke has it—if the Jews had not already existed, the anti-Semites would have had to invent them.

For Adorno, the anti-Semite can’t experience the other; s/he cannot be changed. In a Levinasian sense, he cannot be vulnerable to the other and is incapable of experience because he has negated the world and put a paranoid one in its place. Even if s/he meets a real Jew – Kanye met many – this doesn’t change a thing. The anti-Semite is not in the world; he or she is in his or her own world; in that paranoid reality, the Jew is controlling everything. Only by destroying the Jew, taking away Jewish power, will the anti-Semite feel and know that the world he or she has projected on his or her – see below – (paranoid) world.

Thanks, this is helpful. But black anti-Semitism seems a perverse twist on the German case, that Kanye maybe exemplifies, where the “paranoid reality” springs from (and tries to escape from or fantastically account for) the true reality of anti-black racism

I dont think his anti-Semitism is anything but paranoid. Blaming “the Jews” for “controlling the black voice,” “controlling the media, ” springs from a similar source. Farakahn is a black nationalist and uses similar paranoid ideas and expressions.