When it comes to Jewish humor, self-mockery is not new. Sanford Pinsker argues that Ibn Ezra, the 12th century Rabbi and Torah commentator, used self-mockery to epitomize the comedic state of exile (in general) and the schlemiel (in particular). Self-mockery is found in the classic joke about the schlemiel, the schlimazel, and the nudnik. One spills the soup (the schlemiel), the other is spilled on (the schlimazel), and the third person asks the schlimazel what kind of soup it is (nudnik). Self-mockery has been a way for Jews over the centuries to laugh at bad luck and live on with a sense of…self. Although it might be diminished, it survives. Wit is the power of Jewish humor against powerlessness.

But there is a fine line between self-mockery and self-hatred. And when it moves into the other realm it becomes more sad than funny.

Woody Allen is able to traverse the fine line in many of his movies and in his prose.

For instance, in “The Selections from the Allen Notebooks,” Allen plays on the existential version of the notebook or journal as a space of despair, sickness, and self-hatred:

I believe my consumption has grown worse. Also my asthma. The wheezing comes and goes, and I get dizzy more and more frequently. I have taken to violent choking and fainting. My room is damp and I have perpetual chills and palpitations of the heart. I noticed, too, that I am out of napkins. Will it never stop?

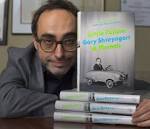

The punch line releases us from the possibility of self-hatred and becomes self-mockery. Gary Shteyngart, in his memoir Little Failure, also tries to tread the same territory as Woody Allen. However, he comes closer to the first lines of Dostoevsky’s Underground Man (“I am a sick, angry man…”) than Allen.

To be sure, Shteyngart associates the essence of writing – and his project – with a tension between joy and self-hatred. But of the two, he admits that without self-hatred and hatred he could not write. It makes writing not only “possible” but “necessary.”

I write because there is nothing as joyful as writing, even when the writing is twisted and full of hate, the self-hate that makes writing not only possible but necessary. I hate myself, I hate people around me, but what I crave is the fulfillment of some ideal. (149)

Following this, he lists several ideals that fail: “my family – Papa hits me; my religion – children hit me”(148). And this leads him to feel rage and informs his main inspiration in America:

But America/Atlanta is full of power and force and rage, a power of force and rage I can fuel myself with until I find myself zooming for the starts with Flyboy and Saturn and Iadara and Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger. (148)

The punchline of this joke is that anger and rage are everywhere in “America/Atlanta” (whether it is the rage of the dispossessed or conservative defense ministers). But the implication is that Shteyngart is parting from Woody Allen’s use of self-mockery. He is not – like many a schlemiel (from Motl to Gimpel or Moses Herzog) a humble and dreamy “little failure” – he is an angry one. Shteyngart’s rage makes him verge on not just self-hatred but also on hatred of others. And, as he notes, it makes his writing “possible” and “necessary.”

When read against the failures of this or that ideal, I can see that there is more going on here than shoulder shrugging. His failures make him feel rage against all of the ideals he was raised with. Although he mocks them (and nearly all of them deal with Jewishness), what we have here is a deep questioning of Jewishness that is based on his negative experiences with it.

At the end of his book, Shteyngart recounts a trip back to Russia with his parents to visit the grave of his grandfather. He recalls a picture of his father (who is enamored with Jewishness and Israel) and mother. He recalls saying Kaddish and even includes the Hebrew. But he has a much different relationship to the Hebrew and his grandfather than does his father.

I can read the prayer, but I cannot understand it. The words coming out of my mouth are gibberesh to me. And they can only be gibberish to my father’s ear as well. (349)

None of this is funny. In fact, its very sad, angry, and solemn.

Shteyngart’s words suggest that Hebrew and Jewishness are, like many other things, failed ideals that he is leaving behind for other ideals. Like a schlemiel, he trips over the words; but, in the end, the fall is fatal not funny:

I chant the gibberish backwards and forwards, tripping over the words, mangling them, making them sound more Russian, more American, more holy. We haven’t found my grandfather’s name, Isaac, amidst the acres of marble covered with Ivans and Nikolais and Alexanders. (349)

The last words of the memoir are in Russian. His Kaddish ends in a foreign language. Unlike his father, he is a realist and sees that there is no point in returning to or trying to find Jewishness for the sake of one’s identity. He mourns it as he mourns his failure of the ideals his father and mother set forth for him. He becomes, for lack of a better word, post-Jewish. His holy tongue is “more Russian, more American.” It’s not Hebrew.

Given what Shteyngart says about writing, one can surmise that what “fuels” the last words of his memoir are hatred and anger. But this seems to pass the fine line between self-mockery and self-hatred. What we are left with is nothing funny. And with this gesture he seems to go from being a little failure who, like many a schlemiel, remains bound to Jewishness (for better or for worse) to an adult who has left it behind for the language of exile.

The other possibility is that this is another kind of Jewishness, but it’s not funny. It seems that, for Shteyngart, the post-modern Jew must be a realist who mourns Jewishness rather than recover it. And the fuel for this gesture is…as he says…rage. And despite all of the comical recountings of his “little failures,” we can say that they are really a façade for his mournful and angry realism. What surprises me most is that I have not found one book review which noticed this. If they did, perhaps his book wouldn’t sell copies.

With this in mind, I’ll leave you with the promotional video for the film which, given this reading, seems to be…besides the point.